|

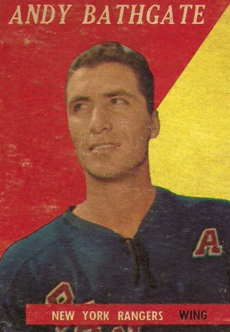

Andy Bathgate

Andrew James Bathgate (August 28, 1932 – February 26, 2016) was a Canadian professional ice hockey right wing who played 17 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for the New York Rangers, Toronto Maple Leafs, Detroit Red Wings and Pittsburgh Penguins between 1952 and 1971. In 2017 Bathgate was named one of the "100 Greatest NHL Players" in history.[1] Playing careerAs a youth Bathgate was offered scholarships to both the University of Denver and University of Colorado to join their hockey teams, but turned them down and instead joined the Guelph Biltmores of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) in 1949.[2] Andy Bathgate was a popular star player of the New York Rangers and also held the honour of being declared the Most Valuable Player of both the NHL and Western Hockey League (WHL). He started his professional career with the Cleveland Barons of the American Hockey League (AHL) in the 1952–53 season. He bounced between the WHL's Vancouver Canucks (not to be confused with the later NHL team of the same name) and the Rangers for two seasons before settling with the Rangers in 1954–55. He played 10 full seasons with the Rangers, where he became a popular player in New York as well as a top-tiered player in the NHL. In 1961–62, Bathgate and Bobby Hull led the league in points, but Bathgate lost the Art Ross Trophy to Bobby Hull because Hull had more goals. Bathgate's career was frustrated by the mediocre play of the Rangers and a nagging knee problem. He was traded to the Toronto Maple Leafs during the 1963–64 season, where he immediately helped Toronto to a Stanley Cup championship. In May 1965, the Maple Leafs traded Bathgate, Billy Harris, and Gary Jarrett to the Detroit Red Wings for Marcel Pronovost, Aut Erickson, Larry Jeffrey, Ed Joyal, and Lowell MacDonald who went to the Toronto Maple Leafs.[3] Bathgate helped the team reach the Stanley Cup Finals in 1965–66. Bathgate was chosen by the Pittsburgh Penguins in the 1967 NHL Expansion Draft, scoring the first goal in the team's history. However after one season, he returned to the WHL's Vancouver Canucks, where he would help lead the team to two consecutive Lester Patrick Cup victories, in 1969 and 1970. His best professional year was 1969-70, scoring 108 points for the Canucks. That performance earned him the George Leader Cup, the top player award in the WHL. Bathgate returned to the NHL's Penguins, playing his last year of North American professional hockey for them in 1970-71. He served in 1971–1972 as playing coach for HC Ambri-Piotta in Switzerland. He came briefly out of retirement three seasons later to play for the Vancouver Blazers of the World Hockey Association (WHA), which he had coached the previous season, but retired for good after 11 games. Bathgate won the Hart Memorial Trophy for the MVP of the NHL in 1958–59 after scoring 40 goals. He is also known for his contribution to the in-game use of masks for goaltenders during games. Renowned for the strength of his slapshot, during a game against the Montreal Canadiens, Bathgate shot the puck into the face of Jacques Plante, forcing Plante to receive stitches. When Plante returned to the ice, he was wearing a mask. That started a trend that led to it and other protective gear becoming mandatory equipment.[citation needed] Stance against spearingIn December 1959, Bathgate produced a controversial article for True magazine in which he warned that hockey's "unchecked brutality is going to kill somebody".[4] The article, titled "Atrocities on Ice", was ghostwritten by Dave Anderson, who was then a sports journalist with the now defunct New York Journal-American, and it appeared in True magazine's January 1960 edition. Bathgate focused mostly on the tactic of spearing, where a player stabs at an opponent with the blade or point of his stick. In a section titled "Andy Bathgate's rogues gallery", six players were highlighted as the most brutal, with their photographs captioned with a short description by Bathgate. These were Detroit's Gordie Howe ("meanest player in the league; uses all the tricks—plus"); Chicago's Ted Lindsay ("seldom drops his stick in a fight"); Montreal's Tom Johnson ("one of the five notorious spearing specialists in the NHL"); Montreal's Doug Harvey ("lucky he doesn't have a spearing death on his conscience"); Boston's Fern Flaman ("he's had too many accidents to believe") and New York's Lou Fontinato ("likes to use the stick but uses his fists in a real fight").[4][5] Responding to the article, Toe Blake, the Montreal Canadiens' head coach, admitted that Montreal players used spearing, but claimed it was purely a defensive tactic "necessary to defend against an illegal play pattern used often by the Rangers." Blake said: "They like to skate into our zone against the defence and drop the puck for a teammate following right behind. Then they skate into our defenceman, blocking him out of the play illegally through interference. Our players have sometimes had to spear to fend off the interfering player and keep in play."[4][6] Doug Harvey also admitted spearing, saying: "Sure, we will spear on occasion. We've got to when they run interference," and that he used it "only for defensive purposes."[4][6][7] Bathgate wrote of the offenders: "None of them seems to care that he'll be branded as a hockey killer."[8] In response the NHL fined him for "comments definitely prejudicial to the league and the game."[9] Speaking in 2010, Bathgate said: "We had an episode where fellas were spearing other players. So I wrote an article with Dave Anderson of The New York Times [sic] called 'Atrocities on Ice.' Red Sullivan, I saw him speared right in front of our bench and have his spleen punctured. It was getting out of hand. I wrote this article and got fined for it. I got fined $1,000—and I was only making $18,000 at the time—so you take that, plus the $1,000 we had to pay into our pension, that's a lot of money out of your pocket. They changed the rule at the end of the year but they still didn't give me my $1,000 back. It burns my (butt) at times, but you have to stand up for it. Sometimes, you've got to speak up for the betterment of hockey because someone was going to get seriously hurt."[10] Post-retirementBathgate owned and managed a 20-acre (81,000 m2) golf course called the Bathgate Golf Centre, while his brother Frank owned a driving range just down the road both on Hwy 10 in Mississauga, Ontario. During the winters he helped coach his grandson's hockey team. He also stated that he was unlikely to play in any more old-timer's games, citing recent hip surgery. "Those old fellas get too serious. They'll start hooking you."[11] The Rangers retired his #9 along with Harry Howell's #3 in a special ceremony before the February 22, 2009, match against the Maple Leafs. Bathgate joined Adam Graves, whose #9 had been hoisted to the Madison Square Garden rafters 19 nights earlier.[12] Graves called Bathgate "the greatest Ranger to ever wear the #9". Personal lifeBathgate was married to his wife Merle Lewis from 1955 until his death in 2016. They had two children, a son named Bill, and a daughter named Sandra Lynn “Sandee”. Bathgate died at the age of 83 on February 26, 2016, in Brampton, Ontario. At the time of his death, he had Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.[13][14] Bathgate's grandson and namesake, Andy Bathgate, born February 26, 1991, was drafted by the Pittsburgh Penguins in the 2009 NHL Entry Draft and previously played for the Birmingham Bulls of the Southern Professional Hockey League.[15] Awards and achievements

Career statisticsRegular season and playoffs

Coaching record

Video clipshttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rov_BdMqnYI See alsoReferences

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Andy Bathgate.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||