|

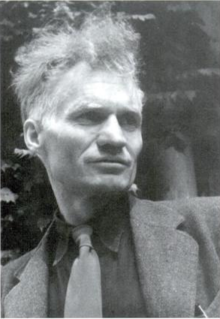

André Charles Biéler

André Charles Biéler CM RCA (8 October 1896 – 1 December 1989)[1] was a Swiss-born Canadian painter and teacher. His work was modernist, at first with strong emphasis on line, later with more interest in light and colour. He is known for his genre pictures of life in rural Quebec. He was the first president of the Federation of Canadian Artists (1942–1944), and was instrumental in the foundation of the Canada Council and the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario. Early yearsAndré Charles Biéler was born in Lausanne, Switzerland on 8 October 1896.[2] His father, Charles Biéler, was director of the Collège Galliard. His mother Blanche was the daughter of the historian Jean-Henri Merle d'Aubigné (1794–1872).[1] Biéler, moved to Paris for twelve years with his parents and brothers, Jean, Étienne, and Jacques, before the whole family immigrated to Canada in 1908. Biéler's father became registrar of the Presbyterian College, Montreal. Biéler studied at Westmount Academy and then the Institut Technique de Montreal. He intended to study architecture.[1] During World War I (1914–1918) Biéler joined the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in 1915. He was wounded and seriously gassed.[1] Artistic training and developmentAfter being released from the army Biéler studied at the Lycée Carnot in Paris.[1] In 1919 he returned to Canada, then went to Florida to recuperate, where Harry Davis Fluhart (1861–1938) gave him art lessons. He received a veteran's grant that allowed him to study under Charles Rosen (1878–1950) and Eugene Speicher (1883–1962) at the Art Students League of New York in Woodstock, New York. He returned to Montreal, where he became acquainted with members of the Beaver Hall Group.[3] From 1922 to 1926 Biéler spent most of his time in Switzerland, studying under his uncle Ernest Biéler, a painter and muralist.[3] He helped his uncle with several frescoes in the town hall of Le Locle in the Canton of Neuchâtel.[1] He also spent some time in Paris, France, and studied at the Académie Ranson with Maurice Denis (1870–1943) and Paul Sérusier (1864–1927). In 1924 Biéler had his first solo exhibition, at the Art Association of Montreal.[3] He lived on the Île d'Orléans in Quebec from 1927 to 1929, where he painted the habitants.[2] He met A. Y. Jackson (1882–1974) at this time.[3] In 1930 Biéler set up a studio in Montreal, earning a living by undertaking commercial commissions and by teaching.[2] He and John Goodwin Lyman founded the Atelier art school, which only lasted for a short period.[3] Biéler and Edwin Holgate led the "Oxford Group" in Montreal, which met in a below-ground room at the Oxford tavern at lunchtime. The group had roughly equal numbers of francophone and anglophone members. Other members were Albert Edward Cloutier, Adrien Hébert, the art critic Jean Chauvin and the editor Carrier.[4] Biéler worked with Jeannette Meunier, a young interior decorator and designer. Through her he became involved in design of theater sets and costumes, furniture, interiors, fabrics and posters. He promoted interior decoration using the homespun textiles made by spinners and weavers from the lower St. Lawrence region. In 1931 Biéler and Jeannette Meunier married.[1] Biéler often visited the Laurentian Mountains on painting expeditions.[3] In 1935 the Biélers moved to Saint-Adèle, a quiet town in the Laurentians.[1] Biéler made some of the illustrations for Kingdom of the Saguenay (1936) by Marius Barbeau.[5][a] ProfessorIn 1936 Biéler became a professor of art at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario. Biéler organized the first conference of Canadian artists in 1941. This led to the foundation of the Federation of Canadian Artists, of which Biéler was the first president.[2] Biéler taught at the Banff School of Fine Arts in the summers of 1940, 1947, 1949 and 1952. In 1953-54 he took a one-year sabbatical from Queen's to study and paint in Europe.[1] Biéler provided impetus that led to the formation of the Canada Council in 1957. He was also the main organizer of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston in 1957, and was its first director.[2] He returned to Europe to travel and paint in the summer of 1959. Biéler retired from Queens University in 1963. With more freedom to travel, he visited Mexico in 1964, 1966, and 1972.[1] Biéler belonged to the Canadian Group of Painters and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. He developed a pneumatic relief printing press, and formed a company that ran the press. In 1957 he received the J. W. L. Forster Award from the Ontario Society of Artists. He was awarded the Canadian Centennial Medal and an honorary doctorate, and in 1987 was made a member of the Order of Canada.[3] André Charles Biéler died in Kingston, Ontario on 1 December 1989.[2] He was survived by his wife Jeannette and four children. His son, Ted Biéler, became a well-known sculptor.[1] WorkStyleBiéler's style was closer to that of contemporary French painters, in particular to the "School of Paris," then to Canadian movements.[2] His early work shows the influence of his uncle Ernest, with the close attention to line and form essential for stained glass and mosaic work.[3] His later paintings, prints, sculptures and murals treat traditional subjects in a modernist style. He made lively genre pictures of life in rural Quebec, showing figures working in groups or gathering around churches, in harmony with the landscape.[3] He has said,

In his later years Biéler reinterpreted many of his earlier sketches in terms of light and colour.[2] Nancy Baele wrote in 1982 of his work,

Selected worksBiéler's major works include:[1]

ExhibitionsBiéler held more than twenty five solo exhibitions in locations that included Geneva, Montreal, Kingston, Quebec City, Edmonton, Calgary, Banff, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto, and San Miguel de Allende in Mexico. Major retrospective exhibitions were held at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston in 1963, showing 115 works, and in 1970. The 1970 retrospective titled André Biéler, 50 years: a retrospective exhibition 1920-1970 traveled to ten galleries in Canada.[1] ReferencesNotes

Citations Sources

|

||||||||||||||