|

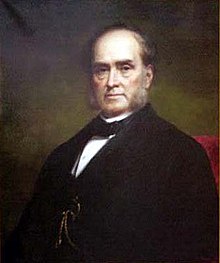

Ambrose Kingsland

Ambrose Cornelius Kingsland (May 24, 1804 – October 13, 1878) was a wealthy sperm oil merchant who served as the 71st mayor of New York City from 1851 to 1853. In 1851, he initiated the legislation that eventually led to the construction of Central Park.[1] Early lifeKingsland was born on May 24, 1804, in New York City. He was the son of Cornelius Kingsland (1768–1815) and Abigail (née Cock) Kingsland (1771–1854).[2] His siblings included Daniel Cock Kingsland (b. 1798), Rebecca Kingsland Sutton (b. 1800), Jane Kingsland Rogers (b. 1802), Clara Ada Kingsland High (b. 1806). He was a member of the old New Jersey Kingsland family who had for nearly 200 years lived in and around Belleville, New Jersey.[3] His maternal grandparents were Isaac Cock (1741–1811) and Charity (née Haight) Cock. His paternal grandparents were Stephen Kingsland and Jane (née Corson) Kingsland.[4] He was the uncle of William M. Kingsland, who owned 1026 Fifth Avenue.[5][6] CareerA successful merchant, Kingsland built businesses in grocery dry goods, sperm oil, shipping and real estate. He held public office as the 71st mayor of New York City from 1851 to 1853, the first mayor to be elected to a two-year term.[3] In 1851, he initiated the legislation that eventually led to the construction of Central Park.[7][8] BusinessKingsland began his career in 1820, in partnership with his brother Daniel C. Kingsland, as a general merchant and commission business, D & A Kingsland, at 49 Broad Street, then 5 Broad Street.[9] The business expanded into sperm oil and international trade. D & A Kingsland operated whaling ships and owned several noteworthy clipper ships, including Typhoon and Western World, operating the Empire Line between New York and Liverpool and the Third Line of New Orleans packets, and entering the China trade around 1850.[1] The firm became D.A. Kingsland & Sutton in 1843, then A. C. Kingsland and Sons, located at No. 55 Broadway in lower Manhattan. Public Office / MayoraltyKingsland was appointed a Commissioner of the Croton Aqueduct in 1848. During the year he held that position the Croton Aqueduct High Bridge commenced operation and the proposal was made to the city to purchase ground for a large new reservoir immediately north of the existing reservoir located at the center of Manhattan.[10] This new reservoir was to become a factor in the creation of Central Park. In 1850 he was nominated as the Whig candidate for Mayor of New York. Kingsland had little political experience and had not previously held elective office. His nomination was part of a concerted initiative undertaken by New York’s business community to mobilize behind a “Union ticket” promoting the Compromise of 1850 as critical to New York’s future prosperity.[11] New Yorkers’ apprehensions about the nation’s growing disunity, and Kingsland’s high standing in contrast with doubts about the integrity of his Democratic opponent, Fernando Wood, contributed to Kingsland’s election by almost 4,000 votes over Wood.[12] Mayor Kingsland's proposal for a Park "on a scale . . . worthy of the City"Since the mid-1840s, articles and editorials had promoted a “great park” in uptown Manhattan, to remedy the inadequacy of Manhattan’s oppressed collection of small downtown parks; to preserve a large swath of greenspace for health and recreation before the opportunity was lost to imminent uptown development; to create a park that would put New York on a par with elegant European cities and their great parks. Both candidates in the 1850 mayoral elections voiced the need for such a park. On May 5, 1851, Mayor Kingsland sent to the Common Council a message setting forth the necessity and benefits of a large uptown park, proposing that a sum be appropriated to procure a park "of sufficient magnitude" to "become the favorite resort of all classes", that "the establishment of such a park would be a lasting monument to the wisdom . . .of its founders".[13] Kingsland's proposal was the first official step in a tortuous two-year process leading to the State legislation that authorized the creation of Central Park. The proposal, that public monies be appropriated to create a large urban park, was a conceptual novelty.[8] Its eventual outcome – the expenditure of nearly $15 million[14](about five times the entire city’s 1851 budget), including the purchase of 760 acres out of one of the nation’s most expensive urban real estate markets, to create the nation’s first large landscaped public park,[15] was revolutionary. Kingsland’s proposal did not specify a location, other than that it should be "in the northern section of the island".[13] Ever since William Cullen Bryant’s seminal 1844 Evening Post editorial, calling for "a new park", suggested the 160-acre Jones Wood (situated on the East River between 66th and 75th streets), subsequent new park advocates formed a consensus around Jones Wood as the best site for such a park.[16] When the Common Council’s Committee on Lands and Places, having endorsed Kingsland’s proposal, chose this location, the pro-park press heartily cheered it.[17][18] The larger, more centrally located alternative option had not yet surfaced. Legislative action was quick, despite strong opposition from fiscal conservatives and downtown commercial interests. The Common Council approved the committee’s choice of Jones Wood and sought State enabling legislation. Albany enacted the Jones Wood bill on July 11, 1851. In the interim, there appeared two significant articles about the park proposal. One, in June 1851, published correspondence between two city officials discussing an alternative site for the park – a tract, much larger than Jones Wood, at the center of Manhattan where the new Croton reservoir was to be located, which would realize economies of combining park and reservoir.[19] The other article was by noted landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing, thanking the mayor for his path breaking message, but forcefully arguing that the Common Council’s choice of Jones Wood was too tame – that a much larger park was needed for Manhattan’s burgeoning population.[20] In light of the emerging appeal of the central alternate site, and mounting opposition to Jones Wood (fueled by Kingsland’s veto of the Battery enlargement, which nettled aldermen who had seen this downtown park enlargement as a quid-pro-quo for supporting the uptown park[8][21]), the Common Council resolved to delay the Jones Wood acquisition to allow time for considering other possible sites. Kingsland appointed a Special Committee on Parks to evaluate other possible sites,[22] primarily the central site. The numerous advantages of the central site (now referred to as Central Park), including five times the acreage of Jones Wood at a lower cost per acre, better accessibility, and a configuration better suited to a long drive through varied scenery, resulted in the Special Committee’s recommendation of the Central Park site in January 1852. Kingsland thereupon suggested the Common Council petition the State legislature to replace the Jones Wood authorization with Central Park authorization.[14] However, the newly elected Democrat dominated Common Council, immobilized by discord between Jones Wood supporters, Central Park supporters, and those opposing any grand uptown park, took no action Eighteen months of public debate, confusion and intense political maneuvering ensued, as the tide of opinion and political support shifted from Jones Wood to Central Park. Despite setbacks, including Kingsland’s successor Mayor Jacob Westervelt’s reticence towards both park contenders,[22] Central Park prevailed. On July 21, 1853, two years after Kingsland’s proposal, the State legislature passed the Central Park Act, the critical legislation ultimately enabling the realization of his clarion call for a park "on a scale that will be worthy of the city".[13][23] Conflict with the “Forty Thieves” Common Council, 1852 The 1851 city elections ended old line Whig domination of the Common Council and resulted in a sweep of the Common Council by Tammany Democrats. Many of them, including one William Magear Tweed, were small businessmen elected to their first term of office. This group of aldermen intended to use their time in office for self enrichment, and were to be known as the “Forty Thieves” Common Council of 1852-1853.Tammany Hall#Political gangs and the Forty Thieves They foreshadowed an era of New York’s history marked by rampant political corruption. Tweed was the leader of these Forty Thieves and later, in the 1860s, graduated to corruption on a grander scale as master of the Tweed Ring. Under the new municipal charter of 1849, there was little Kingsland could do, as mayor, to thwart the corruption. Since the early 1840s, reformers had sought a new city charter to curtail the excessive power of the patronage prone Common Council by transferring some of its executive functions to an independent executive branch (along with other measures). However, reformers hesitated to concentrate power in the mayor’s office.[24] The new charter extended the mayor’s term to two years, but left mayoral power very limited. Executive functions were transferred to nine departments with independently elected heads, leaving the mayor with little executive authority. Mayoral vetoes of Common Council actions could only delay such actions by ten days, after which they could be overridden by a simple majority.[25] Thus, the Forty Thieves easily overrode Kingsland’s numerous vetoes of their graft riddled bills, ordinances and resolutions, which included the sale of properties and the award of contracts, ferry leases and railroad franchises at rigged values, lining aldermanic pockets at the city's expense. Shortly after Kingsland’s term, a new municipal charter was introduced in 1853 enhancing mayoral power through provision of limited executive appointment powers, and a presidential style veto power.[26] Personal lifeKingsland was married to Mary Lovett (1814–1868), whose father, George Lovett, was born in England.[27] Together, they were the parents of eleven children (two died in infancy):[28]

Kingsland died at his home, 114 Fifth Avenue, at 11 o'clock on a Sunday evening, October 13, 1878.[3] In his obituary, The New York Times announced that his death "removes one of the last of that band of old New-York merchants who were in business 50 years ago, and whose names have become interwoven with the history of New-York."[3] ResidencesKingsland's home was at 114 Fifth Avenue (southwest corner at 17th Street),[40][41] now the site of a Banana Republic store.[5] In 1866, Kingsland purchased Hunter Island, now part of Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx,[42] for $127,501.[43] He later purchased a sizeable country home north of the city along the Hudson River in North Tarrytown, present day Sleepy Hollow, New York.[44] His sale of this land to the early steam-engine automotive company, Stanley Steamer, helped open North Tarrytown's 20th century era as a major automotive factory town. DescendantsThrough his son George, he was the grandfather of Helen Schermerhorn Kingsland (1876–1956),[45] who married Augustus Newbold Morris (1868–1928) (the son of A. N. Morris),[46] George L. Kingsland (1885–1952) and Ethel Welles Kingsland (1886–1967), who married Walter Anderton. Through his son Ambrose, Marjorie Kingsland, who married Viscount Robert de Vaulogé in the Church of St. Clotilde, Paris,[47] and Muriel Kingsland, who married Captain Ivan Barrington White (d. 1947) of the British diplomatic service.[48] Through his daughter Augusta Lovett, who married Herman LeRoy Jones, he was grandfather of Mary Jones who married William Bradford and Herman Jones who married Margaret Hone. Through his son Albert, he was the grandfather of Alberto Alexander Kingsland, Albert Harold Kingsland, and Henry C. Kingsland.[39] Through his son Walter, he was the grandfather of Walter F. Kingsland, Jr. who married the Princess Marie Louise of Orléans (1896–1973) in 1928,[49] Harold Lovett Kingsland who married Fernanda Modet y Cuadra, and Arthur Ambrose Kingsland, who married Constance I Vasselier. LegacyA Hudson River waterfront park, Kingsland Point Park, in the Village of Sleepy Hollow, in Westchester County, still bears Kingsland's name, as does Kingsland Avenue in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn, which he helped survey. There is also a Kingsland Avenue in the Baychester section of the Bronx.[50] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||