|

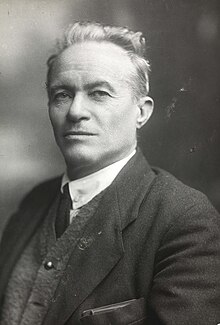

Alexander Tsiurupa

Alexander Dmitryevich Tsiurupa (Russian: Алекса́ндр Дми́триевич Цюру́па; 1 October [O.S. 19 September] 1870 — 8 May 1928) was a Bolshevik leader and Soviet politician. BiographyAlexander Tsiurupa was born in Oleshky, in Taurida Governorate, Russian Empire (now Ukraine). His father was an official.[1] After graduating from a local school, in 1887 he enrolled in the Kherson Agricultural Institute, but in 1893 was arrested and expelled for distributing anti-government literature. He worked as a statistician and agronomist, but in 1895 was arrested again. After his release, he moved to Ufa, where he joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) when it was founded, in 1898, made contact with railway workers, and met Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's in 1900.[2] After Lenin had launched the newspaper Iskra, Tsiurupa became an Iskra agent, in Ufa and, from 1901, in Kharkiv. In 1902, he was arrested and sentenced to three years exile in Olonets.[3] He returned to Ufa in November 1904, and worked as a manager on the estates of Prince Vyacheslav Kugushev,[1] an Ufa landowner whom Tsiurupa persuaded to secretly back the Bolsheviks[4] During the 1905 Revolution, Tsiurupa helped organise strikes, and an underground printing press.[1] After the February Revolution, Tsiurupa was elected to Ufa Committee of the RSDLP. This was an important grain growing district, and during 1917, he organised courses to train inspectors to account for the grain reserves, and arranged for grain supplies to be sent to Petrograd (St Petersburg). In November 1917, after the October Revolution, Tsiurupa was appointed Deputy People's Commissar, and in February 1918 People's Commissar for Food. This meant that during the Russian Civil War, he was responsible for ensuring that grain was collected in areas of the countryside under Bolshevik control, and delivered to towns and for the Red Army, to avert the threat of starvation. With the factories turning out fewer goods that peasant farmers wanted to buy during the disruption caused by war, and paper money being of little value, from 1918 Tsiurupa was organised dozens of armed detachments from the towns who went out and seized grain. He claimed that the squads were sent out only when all other methods had been tried and failed, and denied a rumour that on arrival in a village, they got drunk and went on a rampage. He claimed that they were not simply military detachments, but also propagandists bringing political awareness to the villages.[5] He did, though, concede that sometimes the brigades copied the behaviour of the tsarist police. The historian Orlando Figes describes the activities of these detachments as a "battle for grain ... with the brigades using terror to squeeze out the stocks and the peasants counteracting them with passive resistance and outright revolt" including about 200 violent clashes between peasants and grain collectors in July to August 1918 alone.[6] The detachments were disbanded with the introduction of the New Economic Policy in 1921, after which Tsiurupa was responsible for introducing a new tax system of tax in kind, when Russia lacked a stable currency. There is a story that while travelling by train to organise the seizure of grain, Tsiurupa fainted from hunger. This may just be a myth.[1] But in June 1919, Lenin noted that Tsiurupa was unable to feed his large family on his salary, and ordered that it be doubled.[7] Tsiurupa was Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissar of the Russian Federation in 1921-23. In 1922, he was made head of Rabkrin, succeeding Joseph Stalin, who was appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party - although when Stalin was running Rabkrin, he and Tsiurupa clashed over the issue of food supplies, and Rabrkin did an audit of Tsiurupa's department, which found that it was “very imperfect, cumbersome, expensive, works poorly, (and) requires significant urgent measures” - a view apparently not shared by Lenin.[3] In 1923-25, he was chairman of Gosplan of the USSR. In November 1925, when the people's commissariats for foreign and internal trade were merged, he was appointed People's Commissar for Trade. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1923-28. Despite the high government offices he held, Tsiurupa was not a major political figure. Victor Serge, who met him during the civil war, and was astonished to hear Tsiurupa claim that there was no black market in food, described him as "a man with a splendid white beard and candid eyes ... but he was a captive in offices whose occupants had obviously all primed him with lies."[8]  Tsiurupa died on May 8, 1928, in Mukhalatka village, Crimea) at the age of 57. His ashes were brought buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. His birthplace, Oleshky, was renamed Tsiurupinsk in 1928, but reverted in 2016 to its original name.[9] On 20 March 2023 the Russian occupiers of Oleshky reinstated the name "Tsiurupynsk" for the town; the reason given was that it was "part of the reversal of the renamings committed after the coup d'état in Kyiv."[9] References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||