|

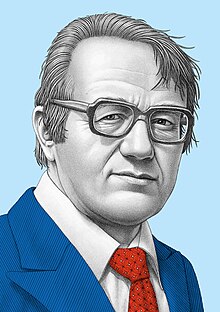

Ales Adamovich

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Adamovich (Belarusian: Аляксандр Міхайлавіч Адамовіч, romanized: Aliaksandr Michailavič Adamovič, Russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Адамо́вич; 3 September 1927 – 26 January 1994) was a Soviet Belarusian writer, screenwriter, literary critic and democratic activist. He wrote in both the Russian and Belarusian languages. Having fought as a child soldier in the Belarusian resistance during World War II, much of Adamovich's work revolved around the German occupation of Byelorussia during World War II and the Belarusian partisan movement. Among his best-known books are Khatyn and The Blockade Book. Adamovich also wrote multiple screenplays, including that of Come and See. A prominent critic of Stalinism and the Soviet system, he supported several democratic causes in the former Soviet Union, including Soviet dissidents, the Inter-regional Deputies Group, the Belarusian Popular Front and President of Russia Boris Yeltsin. Early life and World War IIAleksandr Mikhailovich Adamovich was born 3 September 1927 in the village of Konyukhi in Minsk Region of what was then the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union. Both his parents were doctors.[1] Shortly after his birth, he moved, along with his parents, to the village of Glusha, in Bobruysk Region. During World War II, Adamovich, aged 15, became a partisan unit member from 1943.[2][3] Adamovich resumed his education following the end of fighting in Belarus in 1944. After the war, he entered the Belarusian State University where he studied in the philology department and completed graduate course; he later studied in Moscow at the Higher Courses for Screenwriters and in the Moscow State University.[4] Literary activities Adamovich was a member of the Union of Soviet Writers from 1957, although he disliked the organisation and considered it to be too strongly supportive of the Soviet government.[2] In 1962, Adamovich became an educator of Belarusian literature at Moscow State University, but was fired in 1966 for refusing to sign a letter condemning dissident writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel.[5] In 1976, he was awarded the Yakub Kolas Belarus State Prize in literature for Khatyn. Most of Adamovich's works were about the German occupation of Byelorussia during World War II, with his most well-regarded works including the novella Khatyn and the memoir collection I am from the Fiery Village. For I am from the Fiery Village, Adamovich collaborated with two other Belarusian writers, Janka Bryl and Uladzimir Kalesnik, in interviewing three hundred survivors of the German occupation of Belarus.[3] In 1989, Adamovich became one of the first members of the Belarusian chapter of PEN International (Vasil Bykaŭ was founder and president of the Belarusian PEN). In 1994, following Adamovich's death, the Belarusian PEN Centre created the Ales Adamovich Literary Prize, a literary award to gifted writers and journalists. Political activitiesAdamovich's maternal grandfather, Mitrafan Tychin, in 1930 was arrested and forced into internal exile in the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, alongside his wife and three children. His experiences with hardship under the rule of Joseph Stalin in the 1930s resulted in Adamovich becoming a prominent critic of Stalinism and the Soviet political system.[6] In 1982, Adamovich represented the delegation of the Byelorussian SSR to the United Nations General Assembly.[4] After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, which had significant effects on Belarus, Adamovich actively promoted the disaster's effects among the Soviet ruling elite.[7][8] From 1989 to 1991, Adamovich was a member of the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union, from the anti-communist Inter-regional Deputies Group.[2] Adamovich was also a significant supporter of the Belarusian Popular Front, assisting in the group's founding and operations.[9] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Adamovich chose to remain in Russia, where he had lived since 1986. In Russia, he continued his anti-communist activism, leading to him becoming co-chair of the Memorial organisation. In October 1993, amidst the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, Adamovich was a signatory of the Letter of Forty-Two, indicating his support for Yeltsin remaining in office.[10] Death and legacyAdamovich died on 26 January 1994, at the age of 66, shortly after testifying for a property dispute involving two former literary organisations. According to his wife, the cause of death was a heart attack. Adamovich was remembered by Russian government news agency TASS as a "prominent public activist who devoted much of his strength and energy to the strengthening of democracy in Russia".[2] In accordance with his will, he was buried in Glusha, next to his parents. Adamovich has been posthumously regarded as among Belarus's greatest writers, and his works have received translation into over 20 languages. Svetlana Alexievich, the Belarusian winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature 2015, names Adamovich as her "main teacher, who helped her to find a path of her own".[11] Honours and awards

In 1997 Ales Adamovich was recognized (posthumously) with the "Honor and Dignity of Talent" award (“За честь и достоинство таланта”). Recipients of this noble award include Dmitry Likhachov, Viktor Astafyev, Chinghiz Aitmatov, Vasil Bykaŭ, Fazil Iskander, Boris Slutsky, Bulat Okudzhava. Selected works

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Ales Adamovich.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||