|

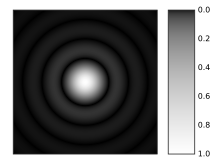

Airy disk    In optics, the Airy disk (or Airy disc) and Airy pattern are descriptions of the best-focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make, limited by the diffraction of light. The Airy disk is of importance in physics, optics, and astronomy. The diffraction pattern resulting from a uniformly illuminated, circular aperture has a bright central region, known as the Airy disk, which together with the series of concentric rings around is called the Airy pattern. Both are named after George Biddell Airy. The disk and rings phenomenon had been known prior to Airy; John Herschel described the appearance of a bright star seen through a telescope under high magnification for an 1828 article on light for the Encyclopedia Metropolitana:

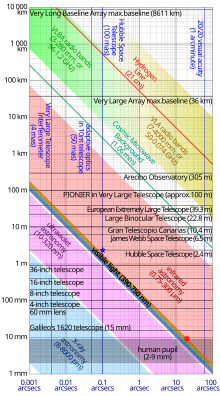

Airy wrote the first full theoretical treatment explaining the phenomenon (his 1835 "On the Diffraction of an Object-glass with Circular Aperture").[2] Mathematically, the diffraction pattern is characterized by the wavelength of light illuminating the circular aperture, and the aperture's size. The appearance of the diffraction pattern is additionally characterized by the sensitivity of the eye or other detector used to observe the pattern. The most important application of this concept is in cameras, microscopes and telescopes. Due to diffraction, the smallest point to which a lens or mirror can focus a beam of light is the size of the Airy disk. Even if one were able to make a perfect lens, there is still a limit to the resolution of an image created by such a lens. An optical system in which the resolution is no longer limited by imperfections in the lenses but only by diffraction is said to be diffraction limited. SizeFar from the aperture, the angle at which the first minimum occurs, measured from the direction of incoming light, is given by the approximate formula:

or, for small angles, simply

where is in radians, is the wavelength of the light in meters, and is the diameter of the aperture in meters. The full width at half maximum is given by Airy wrote this relation as

where was the angle of first minimum in seconds of arc, was the radius of the aperture in inches, and the wavelength of light was assumed to be 0.000022 inches (560 nm; the mean of visible wavelengths).[3] This is equal to the angular resolution of a circular aperture. The Rayleigh criterion for barely resolving two objects that are point sources of light, such as stars seen through a telescope, is that the center of the Airy disk for the first object occurs at the first minimum of the Airy disk of the second. This means that the angular resolution of a diffraction-limited system is given by the same formulae. However, while the angle at which the first minimum occurs (which is sometimes described as the radius of the Airy disk) depends only on wavelength and aperture size, the appearance of the diffraction pattern will vary with the intensity (brightness) of the light source. Because any detector (eye, film, digital) used to observe the diffraction pattern can have an intensity threshold for detection, the full diffraction pattern may not be apparent. In astronomy, the outer rings are frequently not apparent even in a highly magnified image of a star. It may be that none of the rings are apparent, in which case the star image appears as a disk (central maximum only) rather than as a full diffraction pattern. Furthermore, fainter stars will appear as smaller disks than brighter stars, because less of their central maximum reaches the threshold of detection.[4] While in theory all stars or other "point sources" of a given wavelength and seen through a given aperture have the same Airy disk radius characterized by the above equation (and the same diffraction pattern size), differing only in intensity, the appearance is that fainter sources appear as smaller disks, and brighter sources appear as larger disks.[5] This was described by Airy in his original work:[6]

Despite this feature of Airy's work, the radius of the Airy disk is often given as being simply the angle of first minimum, even in standard textbooks.[7] In reality, the angle of first minimum is a limiting value for the size of the Airy disk, and not a definite radius. Examples CamerasIf two objects imaged by a camera are separated by an angle small enough that their Airy disks on the camera detector start overlapping, the objects cannot be clearly separated any more in the image, and they start blurring together. Two objects are said to be just resolved when the maximum of the first Airy pattern falls on top of the first minimum of the second Airy pattern (the Rayleigh criterion). Therefore, the smallest angular separation two objects can have before they significantly blur together is given as stated above by Thus, the ability of the system to resolve detail is limited by the ratio of λ/d. The larger the aperture for a given wavelength, the finer the detail that can be distinguished in the image. This can also be expressed as where is the separation of the images of the two objects on the film, and is the distance from the lens to the film. If we take the distance from the lens to the film to be approximately equal to the focal length of the lens, we find but is the f-number of a lens. A typical setting for use on an overcast day would be f/8 (see Sunny 16 rule). For violet, the shortest wavelength visible light, the wavelength λ is about 420 nanometers (see cone cells for sensitivity of S cone cells). This gives a value for of about 4 μm. In a digital camera, making the pixels of the image sensor smaller than half this value (one pixel for each object, one for each space between) would not significantly increase the captured image resolution. However, it may improve the final image by over-sampling, allowing noise reduction. The human eye The fastest f-number for the human eye is about 2.1,[8] corresponding to a diffraction-limited point spread function with approximately 1 μm diameter. However, at this f-number, spherical aberration limits visual acuity, while a 3 mm pupil diameter (f/5.7) approximates the resolution achieved by the human eye.[9] The maximum density of cones in the human fovea is approximately 170,000 per square millimeter,[10] which implies that the cone spacing in the human eye is about 2.5 μm, approximately the diameter of the point spread function at f/5. Focused laser beamA circular laser beam with uniform intensity across the circle (a flat-top beam) focused by a lens will form an Airy disk pattern at the focus. The size of the Airy disk determines the laser intensity at the focus. Aiming sightSome weapon aiming sights (e.g. FN FNC) require the user to align a peep sight (rear, nearby sight, i.e. which will be out of focus) with a tip (which should be focused and overlaid on the target) at the end of the barrel. When looking through the peep sight, the user will notice an Airy disk that will help center the sight over the pin.[11] Conditions for observationLight from a uniformly illuminated circular aperture (or from a uniform, flattop beam) will exhibit an Airy diffraction pattern far away from the aperture due to Fraunhofer diffraction (far-field diffraction). The conditions for being in the far field and exhibiting an Airy pattern are: the incoming light illuminating the aperture is a plane wave (no phase variation across the aperture), the intensity is constant over the area of the aperture, and the distance from the aperture where the diffracted light is observed (the screen distance) is large compared to the aperture size, and the radius of the aperture is not too much larger than the wavelength of the light. The last two conditions can be formally written as In practice, the conditions for uniform illumination can be met by placing the source of the illumination far from the aperture. If the conditions for far field are not met (for example if the aperture is large), the far-field Airy diffraction pattern can also be obtained on a screen much closer to the aperture by using a lens right after the aperture (or the lens itself can form the aperture). The Airy pattern will then be formed at the focus of the lens rather than at infinity. Hence, the focal spot of a uniform circular laser beam (a flattop beam) focused by a lens will also be an Airy pattern. In a camera or imaging system an object far away gets imaged onto the film or detector plane by the objective lens, and the far field diffraction pattern is observed at the detector. The resulting image is a convolution of the ideal image with the Airy diffraction pattern due to diffraction from the iris aperture or due to the finite size of the lens. This leads to the finite resolution of a lens system described above. Mathematical formulation  The intensity of the Airy pattern follows the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern of a circular aperture, given by the squared modulus of the Fourier transform of the circular aperture:

where is the maximum intensity of the pattern at the Airy disc center, is the Bessel function of the first kind of order one, is the wavenumber, is the radius of the aperture, and is the angle of observation, i.e. the angle between the axis of the circular aperture and the line between aperture center and observation point. where q is the radial distance from the observation point to the optical axis and R is its distance to the aperture. Note that the Airy disk as given by the above expression is only valid for large R, where Fraunhofer diffraction applies; calculation of the shadow in the near-field must rather be handled using Fresnel diffraction. However the exact Airy pattern does appear at a finite distance if a lens is placed at the aperture. Then the Airy pattern will be perfectly focussed at the distance given by the lens's focal length (assuming collimated light incident on the aperture) given by the above equations. The zeros of are at From this, it follows that the first dark ring in the diffraction pattern occurs where or

If a lens is used to focus the Airy pattern at a finite distance, then the radius of the first dark ring on the focal plane is solely given by the numerical aperture A (closely related to the f-number) by where the numerical aperture A is equal to the aperture's radius d/2 divided by R', the distance from the center of the Airy pattern to the edge of the aperture. Viewing the aperture of radius d/2 and lens as a camera (see diagram above) projecting an image onto a focal plane at distance f, the numerical aperture A is related to the commonly-cited f-number N= f/d (ratio of the focal length to the lens diameter) according to

for N≫1 it is simply approximated as This shows that the best possible image resolution of a camera is limited by the numerical aperture (and thus f-number) of its lens due to diffraction. The half maximum of the central Airy disk (where ) occurs at the 1/e2 point (where ) occurs at and the maximum of the first ring occurs at The intensity at the center of the diffraction pattern is related to the total power incident on the aperture by[12]

where is the source strength per unit area at the aperture, A is the area of the aperture () and R is the distance from the aperture. At the focal plane of a lens, The intensity at the maximum of the first ring is about 1.75% of the intensity at the center of the Airy disk. The expression for above can be integrated to give the total power contained in the diffraction pattern within a circle of given size:

where and are Bessel functions. Hence the fractions of the total power contained within the first, second, and third dark rings (where ) are 83.8%, 91.0%, and 93.8% respectively.[13] Classical treatments of the Airy disk and diffraction pattern assume that the incident light is a plane wave that consists of coherent (in phase) photons of the same wavelength that interfere with each other. The famous double slit experiment showed that diffraction patterns could arise even when the coherent photons were so spread out in time that they could not interfere with each other. This led to the quantum mechanical picture that each photon effectively takes all possible paths from a source to a detector. Richard Feynman explained that each path has a complex amplitude that can be thought of as a unit vector that is perpendicular to the path and makes one complete rotation for each wavelength of advance. The detection probability is the square of the sum of the complex amplitudes at the detector. Diffraction patterns arise because the paths sum differently at different detector positions. According to these principles the Airy disk and diffraction pattern can be computed numerically by using Feynman photon path integrals to determine the detection probability at different points in the focal plane of a parabolic mirror.[14]

Approximation using a Gaussian profile The Airy pattern falls rather slowly to zero with increasing distance from the center, with the outer rings containing a significant portion of the integrated intensity of the pattern. As a result, the root mean square (RMS) spotsize is undefined (i.e. infinite). An alternative measure of the spot size is to ignore the relatively small outer rings of the Airy pattern and to approximate the central lobe with a Gaussian profile, such that

where is the irradiance at the center of the pattern, represents the radial distance from the center of the pattern, and is the Gaussian RMS width (in one dimension). If we equate the peak amplitude of the Airy pattern and Gaussian profile, that is, and find the value of giving the optimal approximation to the pattern, we obtain[15] where N is the f-number. If, on the other hand, we wish to enforce that the Gaussian profile has the same volume as does the Airy pattern, then this becomes In optical aberration theory, it is common to describe an imaging system as diffraction-limited if the Airy disk radius is larger than the RMS spotsize determined from geometric ray tracing (see Optical lens design). The Gaussian profile approximation provides an alternative means of comparison: using the approximation above shows that the Gaussian waist of the Gaussian approximation to the Airy disk is about two-third the Airy disk radius, i.e. as opposed to Obscured Airy patternSimilar equations can also be derived for the obscured Airy diffraction pattern[16][17] which is the diffraction pattern from an annular aperture or beam, i.e. a uniform circular aperture (beam) obscured by a circular block at the center. This situation is relevant to many common reflector telescope designs that incorporate a secondary mirror, including Newtonian telescopes and Schmidt–Cassegrain telescopes.

where is the annular aperture obscuration ratio, or the ratio of the diameter of the obscuring disk and the diameter of the aperture (beam). and x is defined as above: where is the radial distance in the focal plane from the optical axis, is the wavelength and is the f-number of the system. The fractional encircled energy (the fraction of the total energy contained within a circle of radius centered at the optical axis in the focal plane) is then given by:

For the formulas reduce to the unobscured versions above. The practical effect of having a central obstruction in a telescope is that the central disc becomes slightly smaller, and the first bright ring becomes brighter at the expense of the central disc. This becomes more problematic with short focal length telescopes which require larger secondary mirrors.[18] Comparison to Gaussian beam focusA circular laser beam with uniform intensity profile, focused by a lens, will form an Airy pattern at the focal plane of the lens. The intensity at the center of the focus will be where is the total power of the beam, is the area of the beam ( is the beam diameter), is the wavelength, and is the focal length of the lens. A Gaussian beam transmitted through a hard aperture will be clipped. Energy is lost and edge diffraction occurs, effectively increasing the divergence. Because of these effects there is a Gaussian beam diameter which maximizes the intensity in the far field. This occurs when the diameter of the Gaussian is 89% of the aperture diameter, and the on axis intensity in the far field will be 81% of that produced by a uniform intensity profile.[19] Elliptical apertureThe Fourier integral of the circular cross section of radius is This is the special case of the Fourier integral of the elliptical cross section with half axes and :[20][21] where See also

Notes and references

External links

|

![{\displaystyle I(\theta )=I_{0}\left[{\frac {2J_{1}(k\,a\sin \theta )}{k\,a\sin \theta }}\right]^{2}=I_{0}\left[{\frac {2J_{1}(x)}{x}}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/546efea8efe27906221b7f353b24a9228ff19887)

![{\displaystyle P(\theta )=P_{0}[1-J_{0}^{2}(ka\sin \theta )-J_{1}^{2}(ka\sin \theta )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/43e77cf6912164bcf59ec7e82c503a752d59df73)

![{\displaystyle E(R)={\frac {1}{(1-\epsilon ^{2})}}\left(1-J_{0}^{2}(x)-J_{1}^{2}(x)+\epsilon ^{2}\left[1-J_{0}^{2}(\epsilon x)-J_{1}^{2}(\epsilon x)\right]-4\epsilon \int _{0}^{x}{\frac {J_{1}(t)J_{1}(\epsilon t)}{t}}\,dt\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c72d72a2dc536d89d33a879a3ff54808eb9662ba)