|

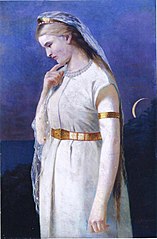

Aino (mythology) Aino (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈɑi̯no]) is a figure in the Finnish national epic Kalevala.[3] DescriptionIt relates that she was the beautiful sister of Joukahainen. Her brother, having lost a singing contest to the storied Väinämöinen, promised Aino's "hands and feet" in marriage if Väinämöinen would save him from drowning in the swamp into which Joukahainen had been thrown. Aino's mother was pleased at the idea of marrying her daughter to such a famous and well-born person, but Aino did not want to marry such an old man. Rather than submit to this fate, Aino drowned herself (or was transformed into a nixie). However, she returned to taunt the grieving Väinämöinen as a perch.[4] The name Aino, meaning "the only one", was invented by Elias Lönnrot who composed the Kalevala. In the original poems she was mentioned as "the only daughter" or "the only sister" (aino tyttönen, aino sisko). National romanticismDuring the national romantic period at the end of the 19th century the mythological name Aino was adopted as a Christian name by Fennoman activists. Among the first to be named so were Aino Järnefelt (Aino Sibelius), born 1871 and Aino Krohn (the later Aino Kallas), born 1878. According to the Finnish Population Register Centre, over 60,000 women have been given the name. It was especially popular in the early 20th century, and the most common first name for women in the 1920s. [1] It has returned to favor in the 21st century; it was the most popular name for girls in Finland in 2006 and 2007.[2] Gallery

References

|

![The earlier 1889 version of the triptych by Gallen-Kallela where Aino had the likeness of a French model[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Akseli_Gallen-Kallela_-_Aino_Triptych_%281889%29.jpg/425px-Akseli_Gallen-Kallela_-_Aino_Triptych_%281889%29.jpg)

![Väinämöinen and Aino, Sigfrid Keinänen [fi], 1896](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Kein%C3%A4nen_V%C3%A4in%C3%A4m%C3%B6inen_ja_Aino.jpg/126px-Kein%C3%A4nen_V%C3%A4in%C3%A4m%C3%B6inen_ja_Aino.jpg)

![Aino, Looking Out to Sea, Johannes Takanen [fi], 1876](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Johannes_Takanen_-_Aino_Looking_out_to_Sea_-_B_I_55_-_Finnish_National_Gallery.jpg/139px-Johannes_Takanen_-_Aino_Looking_out_to_Sea_-_B_I_55_-_Finnish_National_Gallery.jpg)

![Courting of Aino and Aino Drowns Herself, Joseph Alanen [fi], 1908–1910](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/Joseph_Alanen_-_Courting_of_Aino_and_Aino_Drowns_Herself.jpg/351px-Joseph_Alanen_-_Courting_of_Aino_and_Aino_Drowns_Herself.jpg)