|

Adlerhorst

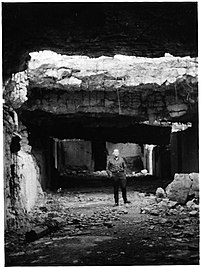

The Adlerhorst ("Eagle's Nest") was a World War II bunker complex in Germany, located near Langenhain-Ziegenberg, the later settlement of Wiesental and Kransberg within the districts of Wetteraukreis and Hochtaunuskreis in the state of Hesse. Designed by Albert Speer as Adolf Hitler's main military command complex, it was reassigned by Hitler in February 1940 to Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring as his headquarters for the Battle of Britain and, later, served as Hitler's only field headquarters during the December 1944–January 1945 Ardennes Offensive. Background There were no official Führer Headquarters before World War II because Hitler used either existing military complexes, or mobile facilities close to the battle lines. Under plans developed by Martin Bormann and architectural designs by Speer, a series of Führer complexes were built. The best known were: the Führerbunker in Berlin; the Berghof complex in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria; and the Wolfsschanze near Kętrzyn in modern-day Poland. Austrian noble Emma von Scheitlein acquired Kransberg Castle in the village of Kransberg in 1926, and used it for society events. Chosen due to its central location as the proposed main military command headquarters of Hitler, it was appropriated by the Nazi government in 1939. Speer immediately began adapting it, designing military-grade infrastructure which was well disguised and adapted to fit-in with its surroundings. ConstructionThe main complex was a collection of seven buildings, in a heavily wooded compound beyond the castle's main entrance.[citation needed] Although each building was designed as an air raid bunker with 3 feet (0.91 m) thick concrete walls, each had the appearance of a traditional locally built Fachwerk (half-timbered) style wooden cottage, complete with second storey dormer windows and flower baskets under a sloped tiled roof. Internally, each was furnished in traditional German style with oak floors, pine wall panelling, utilitarian leather upholstered furniture, and decorated with fringed shade wall lamps and a set of deer antlers. The locals were told that it was an expansion of the air defence zone of Bad Münstereifel. No evidence existed in post-war records to support that the construction phase was anything but successful in covering up the complex's purpose. No notes or briefings were uncovered to suggest that its purpose was known beyond Hitler's inner-circle of its construction or importance.[1][better source needed]  OperationsDuring construction of Adlerhorst, Hitler had used the castle to plan some of the early western campaigns, including the Battle of France and the drive to Dunkirk.[1][better source needed] After the completion of construction, quick approval was given for its operational use. However, after a visit by Hitler in February 1940, he dismissed it as an operational base, as he considered it too lavish for his Spartan taste (and image as a man of the people). Thus, Speer was asked to adapt the complex to meet the needs for use by the Luftwaffe, and specifically to serve as the Luftwaffe headquarters for Hermann Göring during Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of Great Britain. Hitler's Directive No. 16 (the order initiating Sealion) nominated the 'Adlerhorst' (Eagles Nest) at Ziegenberg as the Sealion headquarters. The directive ordered the headquarters for each of the services to set up nearby. The Army and the Navy were to occupy mutual premises in the Army Headquarters at Giessen while the Luftwaffe was to move its headquarters train to Ziegenberg. Ziegenberg is north of Frankfurt and 32 km from Giessen, but it was usual at that time for the German armed service headquarters to be separated by distances up to 50 km during a major operation. For example, Goering's HQ was located 50 km from Felsennest, Hitler's HQ for the invasion of France (10 May-6 June 1940)[2] This distance did not prevent that operation from being successful. Although Hitler didn't move to the purpose-built Führerhauptquartier, he might have done so had the plan been put into execution. His 1,100 man bodyguard, the Fuhrer-Begleitbataillon, plus a 600-man Luftwaffe anti-aircraft detachment, moved to Adlerhorst 5 July 1940 in anticipation of Hitler's arrival. They didn't leave until November 25, 1940.[3] When plans for the invasion of Britain were abandoned in favour of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, the castle and complex were put to use as a rehabilitation centre for soldiers of all ranks, and allocated as Göring's personal retreat.[4] Ardennes OffensiveAfter the 20 July plot attempt on Hitler's life and the abandonment of the Wolfsschanze (Wolf's Lair) due to the advances of the Red Army, Hitler needed a new military base of operations for the forthcoming Ardennes Offensive. Adlerhorst had been given additional security since 1943. Most of the cottages were further disguised with fake evergreen trees as camouflage. From October 1944, Adlerhorst had also become the headquarters of the Commander in Chief of OB West, Gerd von Rundstedt. Hitler arrived at Giessen station on his personal Führersonderzug (train) on 11 December 1944, taking up residence in Haus 1 until 16 January 1945.[1][better source needed] Rundstedt who was to command Operation Wacht am Rhein set up his headquarters near Limburg, Belgium, close enough for the generals and Panzer Corps commanders who were planning the attack, to travel to Adlerhorst in an SS-operated bus convoy that evening. With the castle used to provide for overflow accommodation, the main party settled into Haus 2/the mess. Those present included generals Jodl, Keitel, Blumentritt, Manteuffel and S.S. colonel general Sepp Dietrich. Joined by Hitler, Rundstedt ran through the plans at 05:00 on December 15; the plan that envisaged the attack of three German armies consisting of over 250,000 men. Believing in omens and the successes of his early war campaigns that had been planned at Adlerhorst, Hitler rejoiced in the battles' early successes, taking long walks in the pine forest, regaling his team with his postwar plans and aspirations.[1][better source needed] Shortly after Christmas, Göring arrived and took up residence in the castle. Göring privately suggested to Hitler that a truce be sought via his Swedish contacts. Hitler threatened to have Göring put before a firing squad, before dismissing him as deputy Führer.[1][better source needed] Operation NordwindAfter giving his 1945 New Year's speech from the Pressehaus, Hitler returned to Haus 1 to welcome in the New Year with his close friends and secretarial support team. At 04:00 he walked to the mess to watch the development of Operation Nordwind, his counter-offensive on New Year's Day.[1][better source needed] At midnight, nine Panzer divisions of Heeresgruppe G commanded by Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz attacked Bastogne. Then a faked diversionary attack was mounted by eight German divisions of Army Group Upper Rhine (Heeresgruppe Oberrhein) commanded by Heinrich Himmler, against the U.S. 7th Army and French 1st Army position, which was the thinly stretched line of 110 kilometres (68 mi) long, near Lembach in the Upper Vosges mountains in Alsace; 120 miles (190 km) to the southeast. This defence line had been weakened by U.S. general Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had ordered troops, equipment and supplies north to reinforce the American armies involved in the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes. If successful, the German operation would have opened the way for Operation Zahnarzt, a planned major thrust into the rear of the U.S. 3rd Army. However, the Allies having cracked the German Enigma code machines, each German manoeuvre was either prepared for, or out-flanked by an allied counter-move. This resulted in a bitter attritional campaign that was lost from the 25th January onwards, with the Germans running out of replacement man power, machinery and supplies.[1][better source needed] Abandonment and attempted demolitionOn 6 January 1945, a blockbuster bomb was jettisoned on Ziegenberg by a returning Allied bomber, damaging some buildings and killing four residents. With the Ardennes Offensive failed, and no new military plans or the resources with which to carry them out, the German military high command accepted that the western front was lost. Hitler left Adlerhorst on January 16, 1945, for Berlin. Having been made commander of OB West on March 11, on March 17, Kesselring had sensitive documents and materials removed from the castle, moving himself and the command centre to the OKW house. On March 19, the Allies, once alerted of the original purpose of the complex, and not knowing if Hitler was still in residence, subjected the castle and surrounding area to a 45-minute fire bombing air raid by a squadron of P-51 Mustangs. This resulted in the loss of 10 civilian lives, and the castle and many of the surrounding buildings were damaged, destroyed or set on fire.[1][better source needed] On March 28, with the American army only 12 miles (19 km) away, Kesselring ordered all civilian employees and families of military personnel to evacuate.[1][better source needed]  Capture by Allied forcesThe castle and village were captured by units of the U.S. Army on March 30, 1945. They found the compound burnt and disfigured. The Wachhaus and the Pressehaus escaped demolition, both well preserved and with access to the remaining Adlerhorst bunker complex. Soon afterwards in Operation Paperclip, a British-American detention centre was established in parts of the complex for high-ranking German non-military prisoners of war. It focused on key industrialists, scientists and economists; among those interrogated here were Hjalmar Schacht,[5] Wernher von Braun, Ferdinand Porsche, and the leaders of the IG Farben chemical conglomerate. The highest-ranking of these persons of interest was the complex's original designer Albert Speer.[6] Others interrogated here included many technical, financial and industrial leaders.[7] PresentMost of the castle lay in ruins after the war, but in 1956 the Organisation Gehlen, the U.S.-German intelligence unit that later became the nucleus of the Bundesnachrichtendienst, moved in. It was later followed by V Corps (United States) which operated a NCO academy, and by U.S. intelligence units which directed large parts of its espionage network in communist East Germany from the castle. After a failed restoration attempt in the 1960s, in 1987 with US Army assistance the castle structure was rebuilt, with the stone walls clad in stucco. Returned to the reunified German government in 1990, it was subsequently sold to members of the family of the pre-war owner, and converted into luxury apartments from 1991.[1][better source needed] The Wachhaus and the Pressehaus are both preserved, with the Pressehaus an almost exact replica of the Führerhaus. The Kraftfahrzeughalle motor pool building was not demolished. It was occupied for two years post war by a battalion of U.S. Army Combat Engineers. Converted into a US military hospital in 1977, it was returned to the West German Government in the same year. The half-timbered main hall still stands, and is presently occupied by offices and small businesses.[1][better source needed] The foundations of several houses in the compound have been recycled for modern home and business construction.[1][better source needed] Gallery

See also

ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External links |