|

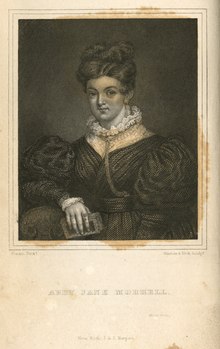

Abby Jane Morrell

Abby Jane Morrell (born February 17, 1809; date of death unknown) was an American writer who produced the first description of sub-Antarctic travel from a woman's perspective. BiographyMorrell was born Abbey Jane Wood in New York on February 17, 1809.[1] Her father, Captain John Wood, died on November 14, 1811, in New Orleans and had been master of the ship Indian Hunter.[1] Her mother remarried in 1814 to a Mr. Burritt Keeler.[1] On June 29, 1824, she married Captain Benjamin Morrell, who was a distant cousin, and became his second wife.[2] They had a first son (born between 1825 and 1828) whom Morrell looked after in New York.[1] However, in her own words, Morrell was determined to accompany her husband on his next voyage in 1829 and succeeded in persuading him after a week of crying.[3] When she and her husband set sail, the son was left in New York with her mother.[1] Voyage On September 2, 1829, they set sail on her husband's fourth voyage of commerce and exploration on the schooner Antarctic.[4] They voyaged from 1829 to 1831 and both wrote accounts of what they saw on their return.[2] Morrell was accompanied by her brother, who is not named.[5] The voyage saw them visit a remarkable number of places around the world, such as the Cape Verde Islands, Tristan da Cunha, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Liberia and South Africa.[6] Morrell kept journals whilst they travelled, which helped to put together her account on her return.[7] Morrell is influenced by the trader perspective in her writings - theirs is a voyage of financial investment.[8] In January 1830, during their travels in the South Pacific,[9] the ship visited the east coast of New Zealand and Morrell went to visit the mission at Paihia, where she was hugely impressed by the work of the English missionaries.[10] Morrell's account is important in Antarctic history, as it the first description by a woman of the subarctic region. On December 5, they put into a harbour visited by James Cook and saw "an enormous number of elephant seals".[11] Many of the things they saw and wrote about are of interest to historians. One episode is the capture of a person called Dako, who appears to have been a leader from the small island of Uneapea (Bali Island), north of West New Britain, Papua New Guinea, who led an attack on their ship.[12] They captured Dako, named him 'Sunday', and he eventually returned to New York with them, and alongside another captive called 'Monday' put them both on display at Tammany Hall and then at Peale's Museum on Broadway.[12] The couple returned to New York in 1831, nine days before their second son was born.[5] Later lifeThere is little documented history for Abby Morrell after 1838: two records, dated 1841 and 1850, place her in New York, but details of her life and eventual death are unknown. She wrote no further books.[13] Reception Morrell's account Narrative of a Voyage to the Ethiopic and South Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Chinese Sea, North and South Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1829, 1830, 1831 was published in New York in 1833 by J. & J. Harper.[2] It was ghost-written by Samuel Knapp, whilst her husband's was completed by poet Samuel Woodworth.[12] The Christian Magazine wrote a double review alongside Emma Willard's Letters from France and Britain, and wrote that "both are the productions of our self-taught countrywomen who [are] ... creditable to their sex".[14] Described today as a "series of self-serving cliches", Morrell's account suffers from no straightforward structure, which could be due to its dual authorship.[15] However, Morrell is compassionate to most: she argues for the reform of sea laws; she sees the non-white people they encounter as human, but nevertheless thinks they should speak English.[15] Like many other writers writing in antebellum America, she approves of colonisation.[16] Unlike many accounts by wives of ship's captains, Morrell's account was aimed at a wide, public audience.[17] Her calls for reform in terms of education, both abroad and on board ship, put her within the context of nineteenth-century social concerns.[17] In more recent scholarship, Morrell's account has been over-shadowed by the longer career of her husband, and academics such as Fairhead[18] have blamed her memoir for opaque representations of her.[19] She was featured on a 4 franc postage stamp issued by the French Southern and Antarctic Lands in 2000.[20] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||