|

88th Illinois Infantry Regiment

The 88th Illinois Infantry Regiment (nicknamed the Second Chicago Board of Trade Regiment) was an infantry regiment from Illinois that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment mustered into service in September 1862 and was engaged at Perryville a month later. The unit subsequently fought at Stones River, in the Tullahoma campaign, at Chickamauga, at Missionary Ridge, in the Atlanta campaign, at Franklin, and at Nashville. The 88th Illinois especially distinguished itself at Stones River, Missionary Ridge, and Franklin. The regiment mustered out of service in June 1865. FormationThe 88th Illinois Infantry Regiment was organized at Chicago on 27 August 1862 to serve three years[1] and mustered into federal service on 4 September 1862. It became known as the "Second Board of Trade Regiment".[2] The original field officers were Colonel Francis T. Sherman, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Chadbourne, and Major George W. Chandler, all of Chicago. Chadbourne resigned on 14 October 1863 and was replaced as lieutenant colonel by Chandler, George W. Smith being promoted major.[3] Chandler was killed in action on 27 June 1864[1] and was replaced as lieutenant colonel by Smith, Levi P. Holden being promoted major. At the time of formation, there was 1 adjutant, 1 quartermaster, 1 surgeon, 2 assistant surgeons, 1 chaplain, 5 sergeant majors, 3 quartermaster sergeants, 1 commissary sergeant, and 1 hospital steward.[4] Colonel Sherman and Lieutenant Colonel Smith were both appointed Brevet Brigadier Generals on 13 March 1865. Captain John A. Bross was promoted lieutenant colonel of the 29th United States Colored Infantry Regiment on 6 April 1864.[1] Bross was fatally wounded while leading his new regiment at the Battle of the Crater on 30 July 1864.[5] Captain Alexander C. McClurg was discharged on 28 June 1864 to accept a promotion to Assistant Adjutant General[1] in the XIV Corps.[6]

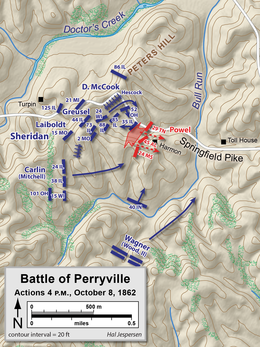

History1862 On 4 September 1862, the newly formed 88th Illinois was ordered to report to Louisville, Kentucky.[8] The regiment camped at Jeffersonville, Indiana, where it received its weapons on 11 September. The unit traveled to Covington, Kentucky, on 12 September and was attached to Colonel Nicholas Greusel's 1st Brigade, Brigadier General Gordon Granger's division, Army of the Ohio. On 21 September, the regiment returned to Louisville where it was assigned to Greusel's 37th Brigade in Brigadier General Philip Sheridan's 11th Division. Other units in the 37th Brigade were the 36th Illinois, 21st Michigan, and 24th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments.[2] Soldiers from the experienced regiments stole equipment from the newly recruited soldiers. When soldiers of the 88th Illinois complained about thefts to the men of the 36th Illinois, the veterans called them "sixty-dollar men" and told them to, "go spend your bounty".[9] The commander of the Army of the Ohio, Major General Don Carlos Buell accepted Charles Champion Gilbert's dubious claim to be a major general and assigned him to lead the III Corps, which included Sheridan's division. [10] On 1 October, Buell launched his army on a campaign against General Braxton Bragg's Confederate army.[2] While marching in the evening of 4 October, the 88th Illinois began singing John Brown's Body and the entire division joined in.[11] The regiment fought at the Battle of Perryville on 8 October 1862.[2] At 4:00 pm, a Confederate brigade attacked Sheridan's position on Peters Hill. The 88th Illinois took position to the right of Captain Henry Hescock's Battery G, 1st Missouri Light Artillery. The 36th Illinois was caught in an awkward position and bore the brunt of the Confederate attack. When its ammunition ran out, the 36th Illinois retreated through the 88th Illinois. This caused the 88th to momentarily waver, but its officers quickly rallied the men; they advanced a short distance and opened fire again. Under fire from an entire Union division, the outnumbered Confederates retreated.[12] Colonel Sherman led the regiment at Perryville where it sustained losses of 8 killed and 35 wounded.[13] The Illinois Adjutant General stated that losses were 4 killed, 5 mortally wounded, and 36 wounded.[2]  The pursuit of Bragg's army lasted until 16 October 1862, then the 88th Illinois marched to Nashville, Tennessee, reaching there on 7 November. The regiment participated in a reconnaissance to Mill Creek on 27 November. The advance to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, commenced on 26 December and the Battle of Stones River occurred on 30 December 1862 – 3 January 1863.[14] At Stones River, the 88th Illinois under Colonel Sherman belonged to Brigadier General Joshua W. Sill's 1st Brigade, Sheridan's 3rd Division, Major General Alexander McDowell McCook's Right Wing XIV Corps, Major General William Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland. The brigade, which consisted of the same units as at Perryville, suffered losses of 104 killed, 365 wounded, and 200 missing. Greusel took command after Sill was killed.[15] On the morning of 31 December a Confederate assault smashed five brigades of McCook's Right Wing.[16] Nevertheless, for 90 minutes, Sheridan's three brigades held out against seven Confederate brigades. This terrific struggle was perhaps the "most determined stand of the entire war".[17] Initially, the brigade was deployed with 88th Illinois, 36th Illinois, and 24th Wisconsin, from left to right, with the 21st Michigan in reserve.[18] After a terrified horde of rabbits hopped through their lines, the 88th Illinois rose up and opened fire on advancing Confederates at a range of 50 yd (46 m), forcing them back. Sheridan soon pulled the 88th Illinois and the 21st Michigan back to a new position at the Harding farm.[19] Finally, the 88th Illinois and the 24th Wisconsin withdrew to a final position in the woods north of the Blanton house.[19] They held out at this position until McCook ordered Greusel to withdraw his brigade. By 10:45 am, Sheridan's division had finally withdrawn, out of ammunition.[20] The regiment suffered losses of 230 killed and wounded, including 4 officers shot,[21] including First Lieutenant Thomas Gullich killed.[1] 1863 The 88th Illinois was attached to 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, XX Corps, Army of the Cumberland from January to October 1863. The regiment remained near Murfreesboro until June, except when it joined an expedition toward Columbia, Tennessee, on 4–14 March. The unit served during the Tullahoma campaign from 24 June to 7 July and joined in the advance across the Tennessee River from 16 August to 22 September. The 88th Illinois fought at the Battle of Chickamauga on 19–20 September.[14] The 88th Illinois under Lieutenant Colonel Chadbourne was attached to Brigadier General William Haines Lytle's 1st Brigade, Sheridan's 3rd Division, McCook's XX Corps, Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland. Lytle's brigade had the same units as at Perryville and Stones River. In the battle, Lytle was killed and the brigade sustained losses of 55 killed, 321 wounded, and 84 missing.[22] On the second day, Sheridan's division received orders to march from the far right flank to the left flank.[23] Soon after, a major Confederate assault broke through the Union center. Colonel Bernard Laiboldt's brigade of Sheridan's division was posted on a commanding hill with its regiments one behind the other. When Laiboldt received orders to advance, he protested leaving such a good defensive position. McCook overruled him and ordered an immediate attack, refusing Laiboldt's suggestion to arrange his regiments into line. After Laiboldt's badly deployed brigade was quickly overwhelmed, Sheridan ordered Lytle's brigade to occupy the hill. The 88th Illinois reached the crest just before the Confederates, while the rest of Lytle's brigade formed to its right. After repulsing the first attack, Lytle's brigade was defeated by a second assault and driven off the field.[24]  From 24 September to 23 November 1863, the 88th Illinois was involved in the siege of Chattanooga. In an army reorganization in October, the regiment was attached to the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, IV Corps, Army of the Cumberland until the end of the war. On 25 November, the unit took part in the Battle of Missionary Ridge.[14] The 88th Illinois was led by Lieutenant Colonel Chandler, the 88th's Colonel Sherman commanded the 1st Brigade, Sheridan led the 2nd Division, Granger commanded the IV Corps, Major General George H. Thomas led the Army of the Cumberland, and Major General Ulysses S. Grant directed the combined forces. The 1st Brigade included the 36th Illinois, 44th Illinois, 73rd Illinois, 74th Illinois, 88th Illinois, 22nd Indiana, 2nd Missouri, 15th Missouri, and 24th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments. The 1st Brigade lost 30 killed, 268 wounded, and 3 missing in the fighting.[25] About 3:00 pm with Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's attack on Missionary Ridge stalled, Grant ordered Thomas to capture the Confederate trenches at the base of the ridge.[26] From left to right, Thomas' division commanders were Absalom Baird, Thomas J. Wood, Sheridan, and Richard W. Johnson. On Sheridan's front, the brigades were Brigadier General George D. Wagner, Colonel Charles Garrison Harker, and Sherman, left to right. When the assault began around 3:40 pm, many of the division, brigade, and regimental commanders were not clear what was the objective.[27] After occupying the rifle pits at the base of the ridge, the men of Wagner's brigade began to climb the ridge without orders. The movement was imitated by Harker's brigade as well as by the other assaulting divisions. Sherman's brigade faced a steeper slope than the two brigades on its left. Colonel Sherman started climbing with his first wave of regiments while sending an orderly to urge the second wave to follow.[28] Carrying the regimental colors, Sergeant John Cheevers led the 88th Illinois up the slope. He was so determined to get to the top first that he leapt over a barricade and landed in a trench full of Confederate soldiers. Though he belatedly realized that they might seize the colors, they simply pushed past him in their haste to get away. When Sherman's brigade cleared the crest of their enemies, the men began cheering wildly.[29] First Lieutenant Charles H. Lane and Second Lieutenant Henry L. Bingham were killed in action.[1] 1864–65 The 88th Illinois participated in the Knoxville campaign from 28 November to 8 December 1863. Subsequently, the unit engaged in operations in East Tennessee until February 1864. The regiment was at Loudon, Tennessee, until April and at Cleveland, Tennessee, through May. The unit took part in the Atlanta campaign from May to September 1864.[14] The 1st Brigade was commanded successively by Colonel Sherman, Brigadier General Nathan Kimball, and Colonel Emerson Opdycke. The 2nd Division was led by Brigadier General John Newton, the IV Corps was commanded successively by Major Generals Oliver Otis Howard and David S. Stanley, the Army of the Cumberland was led by Thomas, and the combined armies were directed by Major General Sherman. The brigade consisted of the same units as at Missionary Ridge, with the 28th Kentucky replacing the 22nd Indiana.[30] The 88th Illinois fought at the Battle of Rocky Face Ridge on 8–11 May, the Battle of Resaca on 14–15 May, the Battle of Adairsville on 17 May, and the Battle of New Hope Church on 25–26 May.[14] First Lieutenant Noah W. Rae was mortally wounded at Adairsville and died 2 June.[1] There were clashes at Pine Mountain on 11–14 June and Lost Mountain on 15–17 June.[14] In the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on 27 June, Newton's division made the main IV Corps effort. The brigades of Wagner and Harker led the assault with Kimball's brigade in close support. Confederate fire was intense and the assault failed with heavy losses.[31] Lieutenant Colonel Chandler was killed in the attack and Major Smith assumed command of the 88th Illinois.[1] During the Battle of Peachtree Creek on 20 July, the Confederates launched a major assault which first struck Newton's division and was repulsed.[32] The regiment participated in the siege of Atlanta from 22 July to 25 August, the flank movement on 25–30 August, and the Battle of Jonesborough on 31 August – 1 September.[14] In September 1864, the 88th Illinois moved to Chattanooga, Whiteside, and Bridgeport, Tennessee, where it performed guard duty. In October, the unit moved to Gaylesville, Alabama before returning to Chattanooga. In November, the regiment moved to Pulaski, Tennessee, and skirmished at the Battle of Spring Hill on 29 November and fought at the Battle of Franklin on 30 November.[2] At Franklin, Opdycke led the 1st Brigade, Wagner commanded the 2nd Division, Stanley led the IV Corps, and Major General John Schofield was in overall command. Wagner put two brigades in advanced positions. After Opdycke argued with Wagner, his brigade was placed in reserve behind the main defense line.[33] When it became apparent that the Confederate army was mounting a mass assault, the commander of one of the advanced brigades begged Wagner to order a withdrawal, but was refused. Consequently, the Confederate attackers routed Wagner's two brigades, and by closely following the fleeing soldiers, broke into the main Union defenses.[34]  Wagner's mob of fleeing Union soldiers, mixed with their Confederate pursuers, swept away Schofield's front-line units, creating a 200 yd (183 m) gap. Because Opdycke's brigade recently had rearguard duty, all the men's rifled muskets were stacked loaded with the bayonets fixed. The soldiers snatched up their weapons and spontaneously made a dash for a second line of breastworks in front of them. Waving his cap, Lieutenant Colonel Smith galloped to the front of the combined 74th and 88th Illinois and led his men forward. Major Thomas W. Motherspaw of the 73rd Illinois yelled, "Forward 73rd to the works!" Seeing his soldiers already rushing ahead, Opdycke belatedly shouted, "First Brigade, forward to the works." In a furious melee, Opdycke's soldiers battled their way through the Carter House buildings to occupy the second line of breastworks. Opdycke's men were joined there by rallied men from the front-line units and Wagner's routed regiments. Packed behind the breastwork four and five men deep, the front rank fired their weapons and passed them back to the rear ranks to be reloaded. The Confederates tried several times to retake the second line, but all attempts were bloodily repulsed in some of the most vicious fighting of the war. The soldiers manned several abandoned cannons and blasted the Confederates at the first line breastwork only 65 yd (59 m) distant. By the end of the day, Opdycke's brigade took 394 Confederate prisoners and captured nine enemy colors.[35] At the Battle of Nashville on 15–16 December 1864, Smith led the combined 74th and 88th Illinois, Opdycke directed the 1st Brigade, Brigadier General Washington Lafayette Elliott commanded the 2nd Division, Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood led the IV Corps, and Thomas directed the Army of the Cumberland. The other units in the brigade were the 36th, 44th, and 73rd Illinois, 24th Wisconsin, and 125th Ohio Infantry Regiments. The brigade lost 8 killed, 39 wounded, and 4 missing at Nashville.[36] On the first day, Elliott's division attacked after the Confederate defenses had been breached elsewhere and the skirmish line was able to capture the enemy position.[37] On the second day, the soldiers of Wood's corps, seeing the left flank Confederate defenses collapse, attacked spontaneously and seized the line of breastworks in their front. The Confederate defenders either surrendered or fled.[38] After pursuing the defeated Confederate army, the 88th Illinois moved to Huntsville, Alabama, where it camped from January to March 1865.[39] The regiment joined an expedition to Bulls Gap, Tennessee, and other East Tennessee operations from 15 March to 22 April.[14] The unit returned to Nashville in May. The 88th Illinois was mustered out at Nashville on 9 June and arrived in Chicago on 13 June. The soldiers received their final pay and discharge on 22 June 1865.[39] During service, the regiment lost 5 officers and 98 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 4 officers and 84 enlisted men by disease, for a total of 191 fatalities.[14] During its existence, 1,542 men were enrolled in the regiment.[40] See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||