|

1954 Italian Karakoram expedition controversy

On 31 July 1954 Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli reached the summit of K2, 8,611 metres (28,251 ft), for the first time on the 1954 Italian expedition to K2 but for over fifty years the 1954 Italian Karakoram expedition controversy dragged on concerning whether the official report written by the expedition's leader, Ardito Desio, gave a true picture of the expedition. That the climbers did indeed reach the summit was never in dispute. Initially there were complaints from one of the members of the expedition, Walter Bonatti, about how he felt the report overlooked the importance of his and Amir Mahdi's roles in enabling the climb to be successful. Bonatti also complained about how he and Mahdi had been treated by the climbers who went on to reach the summit. Later Bonatti argued that the lead climbers' supplemental oxygen would not have run out before they had reached the summit, contrary to what they had stated. As the years went by there was increasing support for Bonatti's claims and criticism of the Italian mountaineering authority, the Club Alpino Italiano (CAI), for its failure to deal with the matter. In 2007, after Desio had died, the CAI at last published a revised official account of the climb which generally found in favour of Bonatti's version of events. However, the CAI was then criticised for going too far in an attempt to placate Bonatti and his supporters. Legal difficulties, 1954–1958When Charlie Houston, who had led the 1953 American K2 expedition, attended the jubilant Italian celebrations for the successful climb he realised that behind the scenes things had not been happy. It soon got into the press that Desio had not been a popular leader – he had been self-centred and autocratic. Riccardo Cassin, who had been excluded from taking part, became involved saying Desio had not wanted to share the focus of attention with anyone else. While Desio was still writing his book legal problems started when he accused the expedition photographer of taking away the film of the expedition. Even after one of the scientists in the party admitted they had taken it through a misunderstanding, Desio did not withdraw his accusation until after he had been sued for defamation. Then the CAI successfully sued Desio for the return of some of the grant they had made and both sides went into print acrimoniously. Desio lost his battles and even had to hand back the Caravella D'Oro trophy he had been awarded. Compagnoni then took the CAI to court to ask to be allocated some of the profits from the film Italia K2[1] which was drawing large audiences – he eventually lost the case in 1958. Bonatti had protested that the film understated (indeed omitted any mention of) the role he and Mahdi had played in carrying vital oxygen up for the summit party and about the emergency bivouac but in the end an acknowledgement was included in the distributed film.[2] Desio's 1954 account of the climbDesio wrote the first official account of the expedition in his 1954 book La Conquista del K2[note 1] but this account was disputed over many years by Bonatti and, eventually, Lacedelli and others. That Compagnoni and Lacedelli had reached the summit of K2 was not in dispute – the issue to begin with was how the lead climbers had treated Bonatti and Mahdi who, high on the mountain, had been carrying up oxygen cylinders for them. Later there was a dispute about whether the oxygen had run out before or after they had reached the summit. Overall, Bonatti claimed Desio's book was neither accurate nor fair. The matter became increasingly controversial with a great deal of press criticism, often uninformed. Desio died in 2001 at the age of 104 and eventually in 2004 the Club Alpino Italiano appointed three experts, called "I Tre Saggi" (the three wise men) to investigate.[4][note 2] In 2007 the CAI published K2 – Una Storia Finita (referred to as "CAI 2007" in this article) which included the Tre Saggi report and accepted, and expanded on, its contents.[6][note 3] In short, the CAI report accepted Bonatti's version of events.[7]  Overall Desio's 1954 book was self-congratulatory in tone and emphasised the scientific work over the climbing.[8] He credited Compagnoni and Lacedelli with writing the chapter about events high on the mountain although Lacedelli later said he took no part in writing the book. Desio himself had directed the climb from Base Camp – he only once went up as high as Camp II on the fixed ropes and never went onto the Abruzzi Ridge. He was in reasonably good radio contact with the climbers however.[9][10] What follows here provides a summary of where Desio's account differs from the account given in the 1954 Italian Karakoram expedition to K2 article which is based on the CAI 2007 report. Desio stated that Camp VIII was established just below 7,700 metres (25,400 ft).[11][note 4] After going down to collect equipment and "two oxygen masks" [sic] from halfway down towards Camp VII (the height of which was not stated),[13][note 5] Bonatti and Mahdi got back up to Camp VIII by noon on 30 July and then continued with Abram carrying the oxygen respirators towards Camp IX which had just been established at 8,100 metres (26,575 ft) and where they were to spend the night.[15] CAI 2007 reported that, whereas Desio had said the plan had been for Camp IX at 8,000–8,100 metres (26,200–26,600 ft), on 30 July this was reduced to 7,900 metres (25,900 ft) to allow the oxygen sets to be carried there in one day. The report quoted Lacedelli as eventually saying Camp IX was actually at about 8,150 metres (26,740 ft) and Bonatti and Mahdi's bivouac was at 8,100 m.[12] Desio's book described how, as night fell,[note 6] Bonatti realised he would not reach Camp IX so he called up to the assault team who told them to go down quickly to Camp VIII. However, Mahdi was unfit even to descend so they dug a snow hole for an overnight bivouac without a tent or sleeping bags.[19][note 7] Mahdi had become severely frostbitten by the time they set off down together at dawn.[21][note 8]  Early in the morning of 31 July, as soon as there was a glimmer of light, Compagnoni and Lacedelli emerged from their tent and were amazed to see a figure below them (they could not tell who it was) heading down the mountain. Starting at about 05:00[note 9] they went down to recover the respirators and started their climb at 06:15, now using supplementary oxygen.[23][note 10] As they approached the summit their oxygen ran out unexpectedly early at a height somewhat above the altitude of Broad Peak[note 11] but overcoming their despair they went on towards the summit still carrying their oxygen sets because it would have been difficult and dangerous to remove them. They did not want to waste time over this and they could use them as a substantial marker for the summit. They reached the summit at 18:00 and set off down after 30 minutes as the sun was about to set.[25] Compagnoni published Uomini sul K2[26] in 1958 which accorded with Desio's version. Bonatti's 1961 autobiography When Bonatti returned to Italy he was disappointed he had not been in the summit party but he had no idea about the cause of the ostracism he would suffer from other mountaineers in the coming decades.[27] Until Bonatti protested, the 1955 feature film Italia K2 had been making no mention of carrying up the oxygen cylinders or the overnight bivouac.[28] Aware that there was whispering behind his back, in 1961 he published his autobiography, Le mie montagne,[29] which included his own account of the expedition.[30] Over the next forty years he followed this up with a series of other books.[31] By 1961 Bonatti was a considerable mountaineering hero and his autobiography was well received but its revelations did not make a big impact at the time. Regarding the K2 climb, Bonatti gave an account from his point of view (which differed from Desio's) but did not directly attack anyone.[32] Bonatti claimed that at Camp VII he had come to realise that Compagnoni had been appointed to lead the summit attempt, though no one had actually told him this. Camp VIII had been sited lower than planned at 7,600 metres (25,000 ft).[33] On 29 July Compagnoni and Lacedelli intended to climb to pitch a small assault tent at about 8,100 metres (26,600 ft) but without oxygen they could only dump their baggage at about 7,700 metres (25,300 ft) before returning to VIII. Bonatti and three other climbers set off from Camp VII to VIII carrying a large amount of supplies and some oxygen cylinders but only Bonatti and Pino Gallotti got through, carrying all four loads of supplies but leaving the oxygen well below Camp VIII.[34] For 30 July it was agreed Compagnoni and Lacedelli would establish Camp IX at about 8,000 metres (26,300 ft) though in the event they placed the camp at 8,100 metres (26,600 ft) at a site that was difficult to locate or reach. Bonatti and Gallotti descended 180 metres (600 ft) to attempt to bring the oxygen up past Camp VIII to the newly established Camp IX, a climb of at least 490 metres (1,600 ft). In fact, as they reached the oxygen, they met Abram and two porters climbing up so they all went up to VIII. By that stage only Bonatti, Abram and Mahdi could contemplate continuing to Camp IX. Eventually Abram had to turn back and darkness fell before Bonatti and Mahdi could locate camp IX.[35] They did not have sleeping bags or a tent and Mahdi was by now in a great panic, stumbling around the mountain slope – they would not be able to get back down to the lower camp and would have to endure an emergency overnight bivouac. Then a light shone a little above them and Lacedelli shouted to leave the oxygen and go down to Camp VIII. The light was turned off and, despite more shouting from those below, no more was heard from those at Camp IX. Bonatti considered the tent had deliberately been positioned to be out of reach. At dawn Mahdi raced down but Bonatti waited until 06:00, in full daylight, before descending, still with no sign of the higher tent or anyone in it. He heard a shout from above but still couldn't see anyone.[36] Summary of claims about altitudes of locations high on K2

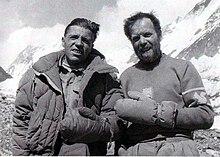

Bonatti said he had to descend 180 metres from Camp VIII to get the oxygen then the plan would have been to climb 490 metres to Camp IX but, because it had been sited higher, 670 metres.[39] Defamation of Bonatti and aftermathDefamation of Bonatti by GiglioOn the tenth anniversary of the expedition the mountaineering journalist Nino Giglio published two articles in a Turin newspaper[note 16] basing his reports on interviews with Compagnoni and Lacedelli and said to be in response to Bonatti's book. Giglio claimed that Bonatti had on the night of 30–31 July not been trying to help his companions but had been secretly trying to beat Compagnoni and Lacedelli to the summit. Moreover, he had deceived Mahdi into accompanying him on this unsuccessful attempt. He had used up some of the bottled oxygen he was supposed to be transporting to Camp IX which was why it ran out early on the successful summit attempt. After Bonatti had shouted up to Camp IX he had refused the offers of help from the lead party and he had descended to Camp VIII leaving Mahdi stranded at the bivouac site so that he got severe frostbite. Compagnoni was quoted as offering to bury the hatchet if Bonatti owned up. In the second article the expedition's liaison officer Mohammad Ata-Ullah was quoted as confirming that Bonatti had tried to persuade Mahdi into joining in with the scheme.[46][47] Even before the time of the newspaper articles such rumours had been believed in some Italian mountaineering circles and Bonatti's 1961 book had been regarded as an untruthful attempt to cover up his misdeeds. Bonatti sued Giglio for defamation and in 1966 he won in court. Bonatti's case was strong – Bonatti, Abram and Mahdi had only been carrying oxygen cylinders and did not have the breathing masks and valves which were up at Camp IX so a summit attempt like this was absurd; also, as confirmed by the climbers at Camp VIII, Mahdi had got down to Camp VIII slightly before Bonatti and had not been abandoned.[48][49] The best argument by the defence was that Bonatti had admitted offering Mahdi inducements to climb higher and had written of fantasising about using the oxygen for himself.[50] All the same, even after the court case Bonatti felt cold-shouldered as a liar and a disruptive element.[51] Bonatti's 1985 book – Robert Marshall's involvement Bonatti's 1985 book, Processo al K2, gave details and transcripts of the court case and a detailed narrative of his version of what had occurred on the mountain, specifically saying Desio's 1954 version was untruthful. Based on the time from when he had seen Compagnoni or Lacedelli at Camp IX on the morning of 31 July to the time they reached the summit, he gave calculations that, he thought, showed there was plenty of oxygen for the ascent and so the claim that it ran out before the summit was false.[52] This depended on discounting Compagnoni's statement that they broke camp at about 05:00 and accepting that Bonatti had heard a shout from someone near Camp IX somewhat before 07:00.[53][54] After reading the book, an Australian surgeon, Robert Marshall, an armchair mountaineer who had long taken an interest in the K2 saga, began investigating. He taught himself Italian just for this purpose and started writing to Bonatti, eventually meeting him.[55][56] He developed the theory that Compagnoni resented Bonatti, the young upstart,[note 17] and had deliberately put Camp IX in a place Bonatti could not reach so that Bonatti would have no chance of being best fitted for the summit party. His theory was that when Mahdi had returned to base camp he told Ata-Ullah of the incitements for him to go as high as possible and about how his frostbite had been caused by the bivouac. Marshall supposed that Ata-Ullah had then confronted Desio demanding an explanation for Mahdi's mistreatment and that then Desio had questioned Compagnoni, his favourite climber, about the frostbite – Compagnoni laid the blame on Bonatti by playing along with the idea that Bonatti was trying for the summit and later went off down ahead of Mahdi. Marshall thought that, when speaking to the inquiry in Pakistan, Desio had laid the blame on Bonatti (believing this to be properly deserved) but encouraged a bland report to be produced so that Italian honour would be maintained.[55] In 1993 Marshall made a discovery of a photograph of Compagnoni (below) taken on the summit which had not been included in La Conquista del K2 where a much poorer image had been shown. According to Marshall Compagnoni has his oxygen set on the ground but he is wearing his breathing mask with its connecting tube still attached to the cylinders. This suggested that Compagnoni was still breathing supplementary oxygen on the summit. Also, the photograph that had been published of Lacedelli seemed to show frost marks on his beard consistent with his mask having recently been taken off (also below).[57][58] Marshall wrote about the discrepancy shown by the photographs and in 1993 the Italian press, intrigued by the involvement of an Australian surgeon, took up the matter.[note 18] The CAI offered to hear Bonatti on the matter but nothing came of the offer. In 1996 Bonatti published K2:Storia di un Caso dealing again with the court case and adding discussion about the photograph. The mountaineering press outside Italy began publishing sympathetic articles.[59] Bonatti published his second autobiography, Montagne di una vita in 1995 with Marshall's involvement who also translated the book as The Mountains of My Life in 2001. It put forward his oxygen theory along with the photographic evidence and suggested the idea that Desio had believed the worst of Bonatti by accepting he had tried for a unilateral attempt on the summit, and treating him unfairly in the book while at the same time giving an account of a well organised expedition.[60] Then Bonatti published K2, la verità: storia di un caso in 2003 which included articles from many experts and journalists supporting Bonatti's case.[61] Lacedelli and Abram become involved after 50 yearsLacedelli, who had largely stayed out of the controversy, coincidentally published his own book K2: Il prezzo della conquista[62] in 2004, the fiftieth anniversary of the climb and quite shortly after Desio's death. Desio is described as an autocratic bully who only got on with Compagnoni. Lacedelli said he had opposed the positioning of Camp IX and, in hindsight, thought it possible it was sited there to hinder any summit aspirations by Bonatti. They had left Camp IX at about 06:00 and set off with the oxygen at about 07:30.[53] However, the oxygen had indeed run out but much nearer the summit than Compagnoni had claimed.[63] Enrico Abram, a professional engineer who had been in charge of the expedition oxygen back in 1954 now wrote to Bonatti to say that the Italian cylinders had been leaking before the summit attempt. Because they also had German "Dräger" bottles that had not leaked Abram had selected those for the summit attempt and they had an extended life of 12 hours – two and a half hours longer than the time Compagnoni said they took to reach the summit. All the oxygen equipment was fitted with a simple on/off tap. When turned on the gas flowed at a fixed rate and, being open-circuit, did not depend on the climber's rate of breathing.[64][65] Second official Club Alpino Italiano reportIn 2004 Roberto Mantovani, editor of the prestigious journal Rivista delle Montagne and curator of Turin's Museo nazionale della montagna, with 24 eminent co-signatories, wrote an open letter to the CAI demanding an immediate inquiry so a report could be produced for the fiftieth anniversary celebrations. The CAI responded by setting up an inquiry under three eminent professors: I Tre Saggi,[note 2] who reported very quickly in a way that almost entirely supported Bonatti and said the CAI should produce a new official account of the expedition.[59][5] So, over fifty years after K2 had been climbed, the CAI produced a book K2: una storia finita[6] (CAI 2007), officially adopting and publishing the Tre Saggi recommendations and issuing their own statements in support.[56] Mantovani himself wrote the section of the book which summarised the conclusions of the Tre Saggi and produced a new account of what was now accepted had happened on the mountain.[66] In brief, this official account (upon which the 1954 Italian Karakoram expedition to K2 article is based) was that (1) Camp IX had been placed 250 metres (820 ft) higher than agreed and on the far side of difficult rocks; (2) Mahdi eventually lost fingers and toes due to severe frostbite caused by the enforced bivouac; (3) after the overnight bivouac Mahdi set off down before Bonatti; (4) Compagnoni and Lacedelli started ascending with supplementary oxygen at about 08:30; (5) they were using Dräger bottles which guaranteed a supply for twelve hours; (6) the summit was reached slightly before 18:00 when there would have been a reserve of oxygen of at least two and a half hours.[67] Other experts' and journalists' viewsBonatti died in 2011, by then, according to Conefrey, "a man acclaimed as one of, if not the, greatest mountaineers of the twentieth century".[68] In Italy there is little appetite to have further recriminations.[69] Viesturs 2009 and Sale 2011 generally accept the revised account.[70][71] A strong aspect supporting the revised account is the seeming unlikelihood of mountaineers carrying up empty oxygen sets when battling to reach an extreme summit.[69][72] Another point of agreement is that Bonatti and Mahdi transporting the oxygen was a tremendous achievement, one that was vital to reaching the summit successfully at the time they did. However, some mountaineering experts question whether the second CAI report is any more correct than the first one.[69][73] There remain difficulties. The argument that the oxygen must have lasted up to the summit supposes that there were no equipment failures – but there could have been leakages or blockages in the supply of what was often unreliable equipment. Also, there could be no certainty that Compagnoni and Lacedelli did not set off using oxygen earlier than 08:30 – Bonatti might simply have not seen them. Indeed, it is quite likely they would have made an early start.[54] When asked why he had still been wearing his oxygen mask on the summit, Compagnoni said that it was just to warm the atmospheric air.[note 19][74] It transpires Abram was probably wrong in saying only German Dräger were used to the summit – Dräger bottles were blue (the Italian type were red) and the film taken on the summit shows one set of red and the other of blue.[75][76] Notes

ReferencesCitations

Works cited

Italian sources and further readingWikimedia Commons has media related to 1954 K2 expedition.

|