|

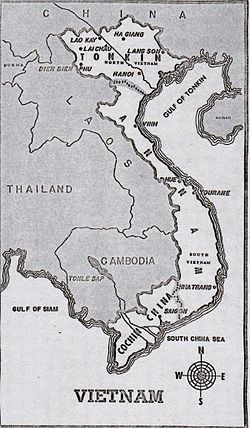

1947–1950 in French Indochina  1947–1950 in French Indochina focuses on events influencing the eventual decision for military intervention by the United States in the First Indochina War. In 1947, France still ruled Indochina as a colonial power, conceding little real political power to Vietnamese nationalists. French Indochina was divided into five protectorates: Cambodia, Laos, Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. The latter three made up Vietnam. In 1946 fighting had broken out between the French forces in Vietnam and the Việt Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh who had declared independence and the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945. The objective of the Việt Minh and other Vietnamese nationalists was full independence from France and unification of the three French protectorates. The Việt Minh was dominated by communists. Initially the United States had little interest in Vietnam and was equivocal about supporting France, but in 1950, due to an intensification of the Cold War and a fear that communism would prevail in Vietnam, the U.S. began providing financial and military support to French forces. Paralleling the U.S. aid program, Communist China also began in 1950 to supply arms, equipment, and training to the Việt Minh. Vietnam played an increasingly important role in the worldwide competition between the communist world, headed by the Soviet Union, and the "Free World" led by the United States. The French suffered severe military defeats in late 1950 which resulted in American military aid being increased to prevent victory by the Việt Minh. The article titled First Indochina War describes the war between the Việt Minh and the French in more detail. This article is preceded by 1940–46 in the Vietnam War and followed by other articles year-by-year. 1947

French Overseas Minister Marius Moutet visiting Vietnam said that the Việt Minh "have fallen to the lowest level or barbarity" and that "before there is any negotiation it will be necessary to get a military decision.[1]

American diplomat Abbot Low Moffat told a British diplomat that the French were facing a disaster in their war in Vietnam.[2]

Secretary of State George C. Marshall in a telegram to the American Embassy in Paris criticized France's "dangerously outmoded colonial outlook and method" but also warned that Việt Minh leader Ho Chi Minh had "direct Communist connections."[3]

France expanded the powers of the Vietnamese-led government of Cochinchina to include self-government on internal affairs and an election for a legislature. The elections were postponed because of civil disorder[4]

France said that 1,855 of its soldiers in the French Far East Expeditionary Corps had been killed or wounded since the beginning of the civil war in December 1946.[5]

French forces had pushed the Việt Minh out of most major towns and cities in northern and central Vietnam, including Hanoi and Huế. Ho Chi Minh maintained his self-proclaimed independent government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Thái Nguyên, north of Hanoi.[6]

Émile Bollaert became France's High Commissioner for Indochina. His priority was to re-open negotiations with the Việt Minh.[7]

The Việt Minh forces near Hanoi were described as having three defense lines. The first was manned by riflemen, the second by soldiers with knives and spears, and the third by men armed with bows and arrows. French military forces in Vietnam totaled 94,000 and 11,000 reinforcements were en route from France. Việt Minh military forces totaled about 60,000 with another 100,000 part-time fighters and militia.[8]

In a diplomatic initiative, Ho had sent diplomat Pham Ngoc Thach to Bangkok, Thailand to seek support from the United States and the American business community. Thach met informally with Lt. Col. William B. Low, the assistant military attaché of the U.S. Embassy, and responded in writing to a series of questions posed by the Americans. Thach emphasized the nationalistic nature of the struggle against French colonialism.

Việt Minh diplomat Pham Ngoc Thach in Bangkok wrote letters to American companies offering economic concessions if they would invest in Vietnam.[9]

Việt Minh Foreign Minister Hoàng Minh Giám appealed to the U.S. for diplomatic recognition of an independent Vietnam and American economic, political, and cultural assistance.[10]

Secretary of State Marshall refused to allow Vice Consul James L. O'Sullivan to meet with Thach in Bangkok. Marshall cited the opposition of France to contacts with the Việt Minh as the reason. Thus, the U.S. had rejected Ho Chi Minh's initiative to gain the support on the United States for an independent Vietnam.[11]

Paul Mus, who had lived for many years in Vietnam, met with Ho Chi Minh at the Việt Minh headquarters in Thái Nguyên 45 miles (72 km) north of Hanoi. Mus proposed a cease fire and a unilateral disarmament by the Việt Minh. Ho said he would be a coward to accept such terms. This was Ho's last meeting with a representative of the French government.[12]

American Vice Consul O'Sullivan in Hanoi reported to Washington that the destruction in northern Vietnam was "appalling." He mostly blamed the Việt Minh for a scorched earth policy, but also French bombing and shelling.[13]

Secretary of State George Marshall asked diplomats in Southeast Asia and Europe their opinion of the Việt Minh and its government, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The responses from Southeast Asia said that patriotism and nationalism were the basis of the Việt Minh's popularity and that the Việt Minh's ties with the Soviet Union were extremely limited. However, from France American diplomats said that Ho Chi Minh "maintains close connections in Communist circles" and that his government, if it became independent, "would immediately be run in accordance with dictates from Moscow."[14] Vice Consul James O'Sullivan in Hanoi responded by saying, "it is curious that the French discovered no communist menace in the Ho Chi Minh government until...it became apparent that the Vietnamese...would not bow to French wishes....[15] It is further apparent that Ho's support (which French to present have consistently underestimated) derives from [the] fact [that] he represents [the] symbol of fight for independence. He is supported because he is acting like [a] nationalist, not because he was or is Communist.[16]

American consuls in Hanoi and Saigon reported to Washington that the French were planning a major military operation against the Việt Minh. They recommended that the U.S. discourage the French from attempting to reimpose the colonial status quo.[17]

French General Jean Étienne Valluy led Operation Léa in an attempt to destroy the Việt Minh and capture or kill its leaders. 15,000 French troops descended upon Việt Minh strongholds north of Hanoi. Ho Chi Minh and military leader Võ Nguyên Giáp barely escaped but the French attack bogged down and Operation Léa was a failure.[18]

In Operation Ceinture The French renewed their attack on Việt Minh strongholds north of Hanoi with a 12,000 man army. They succeeded in briefly capturing much of Việt Minh territory and claimed to have killed 9,500 Việt Minh, probably including many non-combatants, but did not have the manpower to remain to occupy the area. They withdrew their forces, save a few fortified points.[19]

The Hạ Long Bay agreement was reached between the French High Commissioner and former emperor Bảo Đại. The French promised independence to northern Vietnam, but within the French Union and with France retaining control over foreign relations and defence and without unifying Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina, the three French protectorates making up Vietnam. The agreement excluded the Việt Minh from the government. Bảo Đại returned to France and remained there for several months after the agreement was signed while the French attempted to persuade him to return to Vietnam.[20] 1948

American Consul Edwin C. Rendell in Hanoi reported to Washington that the "hard core' of Việt Minh resistance had not been broken by French military offensives. The Việt Minh were stepping up their raids and attacks on French army posts and military convoys.[21]

Ho Chi Minh issued a decree forbidding "one single word or one single line" of criticism of the United States. Ho had not given up on luring the United States to his cause.[22]

Bảo Đại finally returned to Vietnam to attend the signing of a new agreement between France and General Nguyễn Văn Xuân, head of the French-sponsored government of Cochinchina. France recognized the independence of Vietnam within the French Union and endorsed the eventual union of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina into a single state, but France maintained control of defense, foreign affairs, and finances. Bảo Đại returned to France after the signing, refusing to return to Vietnam without receiving additional concessions from France. Xuan established his government in Hanoi. The agreement had little public support.[23]

The U.S. position against the Việt Minh was hardening. The U.S. Consul in Saigon, George M. Abbott, said that a French truce with the Việt Minh "would result in the non-communist elements [in Vietnam] being swallowed up."[24]

George Abbott, the U.S. Consul in Saigon, said prompt action was needed by France to grant real independence to a Bảo Đại government.[25]

The U.S. Department of State said that the policy of maintaining French support for a Western European coalition to contain the Soviet Union took precedence over attempting to persuade France to concede more independence to Vietnamese and end the war.[26] The State Department also concluded that "we are all too well aware of the unpleasant fact that Communist Ho Chi Minh is the strongest and perhaps the ablest figure in Indochina and that any suggested solution which excludes him is an expedient of uncertain outcome. We are naturally hesitant to press the French too strongly or to become deeply involved so long as we are not in a position to suggest a solution or until we are prepared to accept the onus of intervention."[27]

The French had about 100,000 soldiers in Vietnam. The Việt Minh had 250,000 full and part-time fighters and controlled more than one-half the population of the country. The Việt Minh launched frequent attacks on French forces, especially road convoys. In the Saigon area, the French suffered more than 8,000 casualties in 1948 and had suffered more than 30,000 casualties since the beginning of the civil war in 1946.[28] 1949

U.S. Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett said the U.S. should not give its full support to the Bảo Đại government which existed only because of French military forces in Vietnam.[29]

The American Embassy in Paris reported to Washington that the Bảo Đại government was "the only non-communist solution in sight."[29]

France and Bảo Đại concluded the Élysée Accords in Paris which created the State of Vietnam. The Accord reaffirmed Vietnamese autonomy and provided for the union of the three French protectorates of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina, but France retained control of the military and foreign affairs. The Accord was denounced by Ho Chi Minh and generated little support in Vietnam. Bảo Đại returned to Vietnam as Head of State after the agreement was formally approved by the French parliament.[30]

At a Department of State conference, Consul General George M. Abbott said that the only alternatives to a Bảo Đại government were a colonial war or a communist-dominated government of Vietnam.[29]

The Soviet Union detonated a nuclear bomb at a test site, breaking the United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons. The Soviet nuclear test amplified fears by the U.S. and its allies that the Soviet Union might undertake more aggressive action to spread communism to additional countries, including Vietnam.[31]

Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. The triumph of communism in China, resulted in increased fear by the United States that communism would also triumph in Vietnam and that Vietnam would become a puppet state of China and the Soviet Union.[32] 1950

A U.S. Department of Defense Committee recommended that the U.S. expend $15 million on military aid to combat communism in Vietnam. Secretary of State Dean Acheson said that U.S. military aid might be "the missing component" in defeating communist insurgency in Vietnam. Thus, the U.S. was preparing to become financially involved in the conflict in Vietnam.[33]

Eight Chinese military advisers left Beijing to travel to North Vietnam and advise and assist the Việt Minh. They would begin work in March.[34]

Communist China and the Soviet Union extended diplomatic recognition to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as the sole legitimate government authority of all Vietnam. Both promised military and economic assistance to the Việt Minh.[35]

Reflecting the strong anti-communist views in the U.S., The New York Times said that "the disciplined machinery of international communism, directed by Moscow, is carrying out perhaps the most brilliant example of global political warfare so far known by draining the potential strength of France in the Indo-China civil war." The newspaper further reported that "the French might be able to hold off a concerted communist threat [in Vietnam] if properly equipped.[36]

Việt Minh leader Ho Chi Minh arrived in Beijing, China. The trip had taken him nearly a month during which he had walked for 17 days from Vietnam to reach southern China. Chinese leader Mao Zedong was not in Beijing, but Liu Shaoqi promised Chinese assistance to Ho.[37]

Secretary of State Acheson announced U.S. diplomatic recognition of the Vietnamese government of Bảo Đại called the State of Vietnam. Acheson promised economic and military aid to France and the Bảo Đại government. Thus, the U.S., although long skeptical of the suitability of Bảo Đại as a leader and France's colonial rule of Vietnam, came down on the side of both.[38]

Ho Chi Minh, after visiting China, arrived in Moscow, Soviet Union. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was distrustful of Ho's communist credentials and declined to provide Soviet aid to the Việt Minh. Meeting with Mao in Moscow, however, the Chinese leader offered "all the military assistance Vietnam needed in its struggle against France."[39]

U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson said that Ho Chi Minh was "the mortal enemy of native independence in Indo-China."[40]

France officially requested military and economic aid from the United States for Indochina. The materials and equipment the French requested totalled $94 million.[41]

U.S. Ambassador Loy Henderson said that "the Bảo Đại government...reflects more accurately than rival claimants the nationalist aspirations of the people" of Vietnam. In reality, Bảo Đại's State of Vietnam controlled less than one-half the land and people of Vietnam.[42] In disagreement with Secretary of State Acheson, the State Department's head of the Far Eastern Division, W. Walton Butterworth said economic and military aid to the French and Bảo Đại's government of Vietnam were not "the missing components" in solving the problem of Vietnam. He warned that it would be a "dangerous delusion" to believe that aid to Vietnam would be as effective as had been American aid to Greece in fending off a communist insurgency.[36] Butterworth would soon be replaced by Dean Rusk.

French officials told the American Embassy in Paris that without American aid, they might find it necessary to withdraw from Vietnam." In the words of historian Ronald H. Spector, "In time, avoiding French defeat would become more important to the United States than to France."[43]

R. Allen Griffin headed a U.S. delegation visiting Vietnam to recommend priorities for United States economic aid to Vietnam.[44]

Ships of the United States Seventh Fleet and the commander of the Seventh Fleet visited Saigon. It was both an expression of support for France and a show of force.[44]

Amid a growing consensus in the United States that U.S. aid to contain communism in Indochina was necessary, State Department diplomat Charlton Ogburn sounded a cautionary note. "The trouble is that none of us knows enough about Indochina and "we have had no real political reporting from there since [Charles E.] Reed and [James L.] O'Sullivan left two years ago." Ogburn said the Việt Minh had fought the French to a draw and were unlikely "to wilt under the psychological impact of American military assistance." Even if defeated, the Việt Minh could return to guerrilla tactics and bide their time."[45]

U.S. President Harry Truman received and would later approve NSC 68, a secret policy paper prepared by U.S. foreign affairs and defense agencies. NSC 68 expressed an apocalyptic vision of the "design" of the Soviet Union to achieve world domination. This view was bolstered by the recent victory of communist forces in China and by domestic fears of communism, especially those aroused by Senator Joseph McCarthy and Congressman Richard Nixon. The report advocated a massive increase of 400 percent in U.S. budgets for an expansion of the U.S. military and intelligence agencies, plus increased military aid to allies. In the words of a scholar, "NSC-68 provided the blueprint for the militarization of the Cold War."[46][47]

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff wrote Secretary of Defense Johnson that French Indochina Vietnam was "a vital segment in the line of containment of communism stretching from Japan southward and around to the Indian peninsula." The Chiefs said that the fall of Indochina to communism would result in the fall of Burma and Thailand and probably the fall of the Philippines, Malaya, and Indonesia. This was one of the first expressions of the so-called domino theory which would become a prominent determinant in U.S. policy.[48]

The liberal American magazine The New Republic said "Southeast Asia is the center of the cold war....America is late with a program to save Indo-China. But we are on our way."[49]

Acheson told the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee "The French have to carry [the burden] in Indochina, and we are willing to help, but not to substitute for them....we want to be careful...that we do not press the French to the point where they say 'All right, take over the damned country. We don't want it.' and put their soldiers on ships and send them back to France."[50]

The U.S. Department of State announced that, following consultations with France by Secretary of State Acheson, the U.S. would fulfill Acheson's earlier promise and provide military and economic aid to Southeast Asia, especially to the government of Bảo Đại. In the words of The Pentagon Papers, "The United States thereafter was directly involved in the developing tragedy in Vietnam."[51]

Liu Shaoqi, Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist party, instructed the Chinese military to develop a plan to assist the Việt Minh. This plan would include both training and equipment. Within a few months Chinese aid would total 14,000 guns, 1,700 machine gun, and other equipment which were supplied by the dedicating 200 trucks to transport goods from southern China into northern Vietnam on roads under the control of the Việt Minh. By fall General Giap had a fighting force capable of taking on the French forces.[52]

The Korean War began, reinforcing the U.S. view that a monolithic communism directed by the Soviet Union was on the offensive in Asia and threatening to overthrow governments friendly to the United States and its allies.

The first American military aid to French forces in Vietnam arrived in Saigon in 8 C-47 transport airplanes. President Truman had ordered the aid in response to the North Korean attack on South Korea. The prevailing view in the United States was that communism was monolithic and communist activity was coordinated worldwide. Thus, the attack on South Korea caused the U.S. to become more concerned about the Việt Minh insurgency in Vietnam.[53] Việt Minh forces were estimated to have grown to 250,000 personnel, including 120,000 in regular units organized into divisions. The remaining troops were regional and popular and primarily concerned with defense and security. An estimated 15,000 Chinese, in both Vietnam and China, assisted the Việt Minh with training, technicians, and advisers. The French had about 150,000 soldiers in Vietnam. The pro-French Vietnamese army numbered about 16,000[54]

The first U.S. military advisers to Vietnam arrived in Saigon. The complement of the Military Assistance Advisory Group for Indochina was 128 persons but that number would not be in-country for several months. The task of the MAAG was to supervise and monitor the distribution of U.S. military aid to the French military in Vietnam.[55]

The Melby-Erskine Mission to Vietnam submitted its report to the U.S. government after a visit to Vietnam. The team was headed by the Department of State's John F. Melby and Marine Corps general Graves B. Erskine. It was one of the first American missions to Vietnam to assess the struggle of communist insurgents against French colonial rule. The team's assessment of French efforts was very pessimistic and they advised major changes in the French approach, but also recommended providing the military aid France was requesting. Their policy recommendations were neither heeded nor communicated to the French.[56]

General Giap, commander of Việt Minh military forces, attacked a French post at Đông Khê in northern Vietnam with 5 regiments. The post was taken two days later and most of the defenders, two French Foreign Legion companies, were killed. The capture of Đông Khê left the large French garrison at Cao Bằng, 15 miles north, isolated.[57]

The French retreat from Cao Bằng was a disaster. The Việt Minh repeatedly ambushed the convoys and the French suffered 6,000 casualties of whom 4,800 were dead or missing. Only 600 French soldiers reached safety. Of the 30,000 Việt Minh engaged in the battle, 9,000 may have been killed.[58]

The Joint Strategic Survey Committee in a report for the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff said that "The long term solution to the unrest in Indochina lies in sweeping political and economic concessions by France" and "the more aid and assistance furnished to France before reforms are undertaken, the less the probability that France of its own accord will take the necessary action." The study said that Vietnam was not important enough to warrant military intervention by the United States.[59]

U.S. Army Brigadier General Francis G. Brink assumed command of the U.S. military advisory group (MAAG) in Saigon.[60]

French defeats in Vietnam occasioned a large number of appraisals of U.S. policy. U.S. Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins said that the US should be prepared to "commit its own armed forces to the defense of Indochina." Others appraisals were more skeptical about an increased U.S. commitment to Vietnam.[61]

The Việt Minh had pushed the French out of its most northerly outposts and the Chinese border area was now under their control. There was panic among French residents of Hanoi and contingency plans were made to evacuate French citizens from the city.[62]

U.S. President Truman approved an additional $33 million in aid for the French in Vietnam. Included in the aid were 21 B-26 bombers which France had requested.[63]

The Pau conference between the French and Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian representatives concluded. The French made concessions to the desire of the Indochinese for full independence, but retained a veto over many governmental functions.[64]

France concluded an agreement with the Bảo Đại government in Da Lat to create an independent Vietnamese army. However, most of the officers and non-commissioned officers of the army would be French. Most Vietnamese serving in the French army were transferred to the new Vietnamese army. Despite the increasingly important role of the U.S. in supporting the French in Indochina, the U.S. was not invited to participate in the Dalat discussions.[65] See alsoReferences

|