|

Æthelstan A Æthelstan A (/ˈæθəlstæn ˈeɪ/) is the name given by historians to an unknown scribe who drafted charters (or diplomas),[a] by which the king made grants of land, for King Æthelstan of England between 928 and 935. They are an important source for historians as they provide far more information than other charters of the period, showing the date and place of the grant, and having an unusually long list of witnesses, including Welsh kings and occasionally kings of Scotland and Strathclyde. The Æthelstan A charters commence shortly after King Æthelstan conquered Northumbria in 927, making him the first king to rule the whole of England. The diplomas give the king titles such as "King of the English" and "King of the Whole of Britain", and this is seen by historians as part of a rhetoric which reflected his master's claim for a new status, higher than previous West Saxon kings. The diplomas are written in elaborate Latin known as the hermeneutic style, which became dominant in Anglo-Latin literature from the mid-tenth century and a hallmark of the English Benedictine Reform. Scholars vary widely in their views of his style, which has been described as "pretentious"[2] and "almost impenetrable",[3] but also as "poetic"[4] and "as enduringly fascinating as it is complex".[5] Æthelstan A ceased to draft charters after 935, and his successors returned to a simpler style, suggesting that he was working on his own rather than being a member of a royal scriptorium. BackgroundAfter the death of Bede in 735, Latin prose in England declined. It reached its lowest level in the ninth century, when few books and charters were produced, and they were of poor quality.[6] King Æthelstan's grandfather, Alfred the Great (871–899), embarked on an extensive programme to improve learning, and by the 890s the standard of Latin in charters was improving.[7] Few charters survive from the reigns of Alfred and his son, Edward the Elder (899–924), and none from 909 to 925.[8] Until then, charters had generally been plain legal documents, and King Æthelstan's early diplomas were similar.[9] Until about 900, diplomas appear to have been drawn up in varying traditions and circumstances, but in later Anglo-Saxon times (c. 900–1066) charters can be more clearly defined. According to Simon Keynes:

Identity of Æthelstan AIn the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries there was a debate among historians as to whether late Anglo-Saxon charters were produced by a royal chancery or by monasteries on behalf of beneficiaries. In the 1910s, W. H. Stevenson argued that charters in different areas of England were drawn up by the same hand, which would be unlikely if they were drawn up locally, supporting the case that the writers were royal clerks. The German scholar Richard Drögereit followed this up in 1935 by examining original charters between 931 and 963, and identified three scribes from their handwriting, whom he called Æthelstan A, Æthelstan C and Edmund C. Other charters which only existed in copies he allocated to these and other scribes on the basis of their style.[11] In 2002 Keynes listed twenty "Æthelstan A" charters, of which two are original and the rest copies.[12] The boundary clauses of the Æthelstan A charters were written in correct Old English, so it is unlikely that he was of foreign origin.[13] The witness lists of the Æthelstan A charters consistently place Bishop Ælfwine of Lichfield in Mercia in a higher position than his rank warranted. King Æthelstan was probably brought up in Mercia, and in Sarah Foot's view he was probably intimate with Ælfwine before King Edward's death; as Ælfwine disappeared from the witness lists at the same time as the Æthelstan A charters ended, she suggests that he may have been Æthelstan A.[14] Keynes thinks it more likely Æthelstan A was a king's priest from Mercia, who acquired his learning in a Mercian religious house and respected Ælfwine as a fellow Mercian; that Æthelstan A entered Æthelstan's service before he became king and was in permanent attendance on him.[15] David Woodman also considers a Mercian origin likely, pointing out that some Mercian ninth-century charters have borrowings from Aldhelm, an important source of Æthelstan A's style. Woodman also puts forward the alternative idea that Æthelstan A had a connection with Glastonbury Abbey in Wessex, which appears to have been a centre of learning at this time, and certainly housed many of the texts which informed Æthelstan A's idiosyncratic Latin style.[16] Significance of the charters The first charter produced by Æthelstan A in 928 described the king as rex Anglorum, "king of the English", the first time that title had been used.[b] By 931 he had become "king of the English, elevated by the right hand of the Almighty to the throne of the whole kingdom of Britain". Some charters were witnessed by Welsh kings, and occasionally by the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde, signifying acceptance of Æthelstan's lordship. In Keynes's view, it cannot be a coincidence that the charters commenced immediately after the conquest of Northumbria, and Æthelstan A's primary aim was to display the "grandeur of Æthelstan's kingship". Foot argues that the king's inner circle quickly seized on the potential of the conquest for "ideological aggrandizement of the king's public standing". To Keynes, the diplomas "are symbolic of a monarchy invigorated by success, developing the pretensions commensurate with its actual achievements and clothing itself in the trappings of a new political order." He sees the fifty years from 925 to 975 as "the golden age of the Anglo-Saxon royal diploma".[19] Before 928 charters had been produced in various ways, sometimes by royal priests, sometimes by other priests on behalf of the beneficiaries. Æthelstan A was solely responsible for the production of charters between 928 and 934. King Æthelstan thus took unprecedented control over an important part of his functions. In 935 Æthelstan A shared the work with other scribes, and he then apparently retired.[20] His charters have exceptionally long witness lists, with 101 names for a grant by the king to his thegn Wulfgar at Lifton in Devon in 931, and 92 for a grant to Ælfgar at Winchester in 934. The witness lists of King Æthelstan's father and grandfather were much shorter, with the longest in Alfred the Great's reign having only 19 names. In John Maddicott's view the long lists in Æthelstan's reign reflect a change of direction to larger assemblies. The king established a novel system, with his scribe travelling with him from meeting to meeting, and a uniform format of charters.[21] The dating clause showed the regnal year, the indiction, the epact, and the age of the moon. In Keynes's view: "Nothing quite like them had been seen before; and they must have seemed magnificent, even intimidating, in their formality and their grandeur."[22] A unique feature is that three charters in favour of a religious community require it to sing a specified number of psalms for the king, indicating a particular interest in psalmody by the king or scribe.[23] Frankish annalists usually recorded a king's location at Easter and Christmas, but this was not a practice of English chroniclers, and the only period in the tenth and eleventh centuries for which historians can construct a partial itinerary of the king's movements is provided by the location of assemblies recorded in Æthelstan A's charters of 928 to 935. Other charters rarely named the place of assembly, apart from a group in the 940s and early 950s known as the "alliterative" charters.[24] In 935 a new simplified format was introduced by other scribes, apparently while Æthelstan A was still active, and became the standard until the late 950s. This coincided with the disappearance of Wulfstan I, Archbishop of York from the witness lists, and greater prominence of the Bishops of London and Bishop of Winchester, and the new format may have reflected a change of outlook at court.[25] As charters were no longer written in Æthelstan A's distinctive style when he ceased producing them, it is likely he was working on his own rather than heading a royal scriptorium.[26] Style of the chartersThe standard of Latin prose improved in the tenth century, especially after about 960, when the leaders of the Benedictine reform movement adopted the elaborate and ornate style of Latin now called by historians the hermeneutic style. Use of this style, influenced especially by Aldhelm's De virginitate, dates back to King Æthelstan's reign. Æthelstan A borrowed heavily from Aldhelm; he would not copy whole sentences, only a word or a few words, incorporating them in a structure reminiscent of Aldhelm's works.[27] In Woodman's view, "Æthelstan A" varied the language in each charter out of a delight in experimentation and to demonstrate his literary ability.[28] The florid style of seventh-century Irish texts known as Hiberno-Latin was influential on the Continent due to the work of Irish missionaries in Europe. Some works were known to English writers such as Aldhelm in the same century, but it is likely that Æthelstan A learnt of them from continental scholars such as Israel the Grammarian, who brought texts influenced by Hiberno-Latin to King Æthelstan's court.[29] Woodman states that: "whilst it is true that the main impetus for the literary revival of Latin prose occurred from the mid-tenth century, the beginnings of this style of Latin can actually be found rather earlier and in the most unlikely of places. In fact it is diplomas of the 920s and 930s that are the first to display this distinctive Latin in its most exuberant form."[30] According to Scott Thompson Smith Æthelstan A's diplomas "are generally characterised by a rich pleonastic style with aggressively literary proems and anathemas, ostentatious language and imagery throughout, decorative rhetorical figures, elaborate dating clauses, and extensive witness lists. These are clearly documents with stylistic ambitions."[31] Few listeners would have understood them when they were read out at royal assemblies.[32] In Charter S 425 of 934, the second of the two originals to survive, Æthelstan A wrote (in Smith's translation):

In S 416 of 931, the first original to survive, after the boundary clause in Old English, he reverted to Latin for the anathema against anyone who set aside the charter:

Some scholars are not impressed. Michael Lapidge describes Æthelstan A's style as "pretentious",[2] and according to Mechtild Gretsch the diplomas

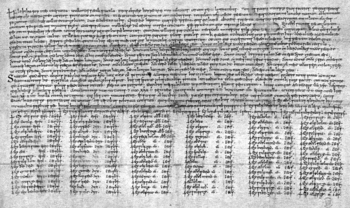

On the other hand, Drögereit describes Æthelstan A's style as having a "poetic quality",[4] and Woodman describes him as an "author of no little genius, a man who not only overhauled the legal form of the diploma but also had the ability to write Latin that is as enduringly fascinating as it is complex." In Woodman's view: "Never before had the royal diploma's rhetorical properties been exploited to such a degree and it seems no coincidence that these documents appeared following King Æthelstan's momentous political conquest of the north in 927."[35] List of chartersKeynes listed the Æthelstan A charters in Table XXVII of his Atlas of Attestations.[36][c] The charters are in the script called "Square minuscule ('Phase II')", with a Latin text and the boundary clause in the vernacular.[37] Charters

See alsoNotes

References

Sources

|